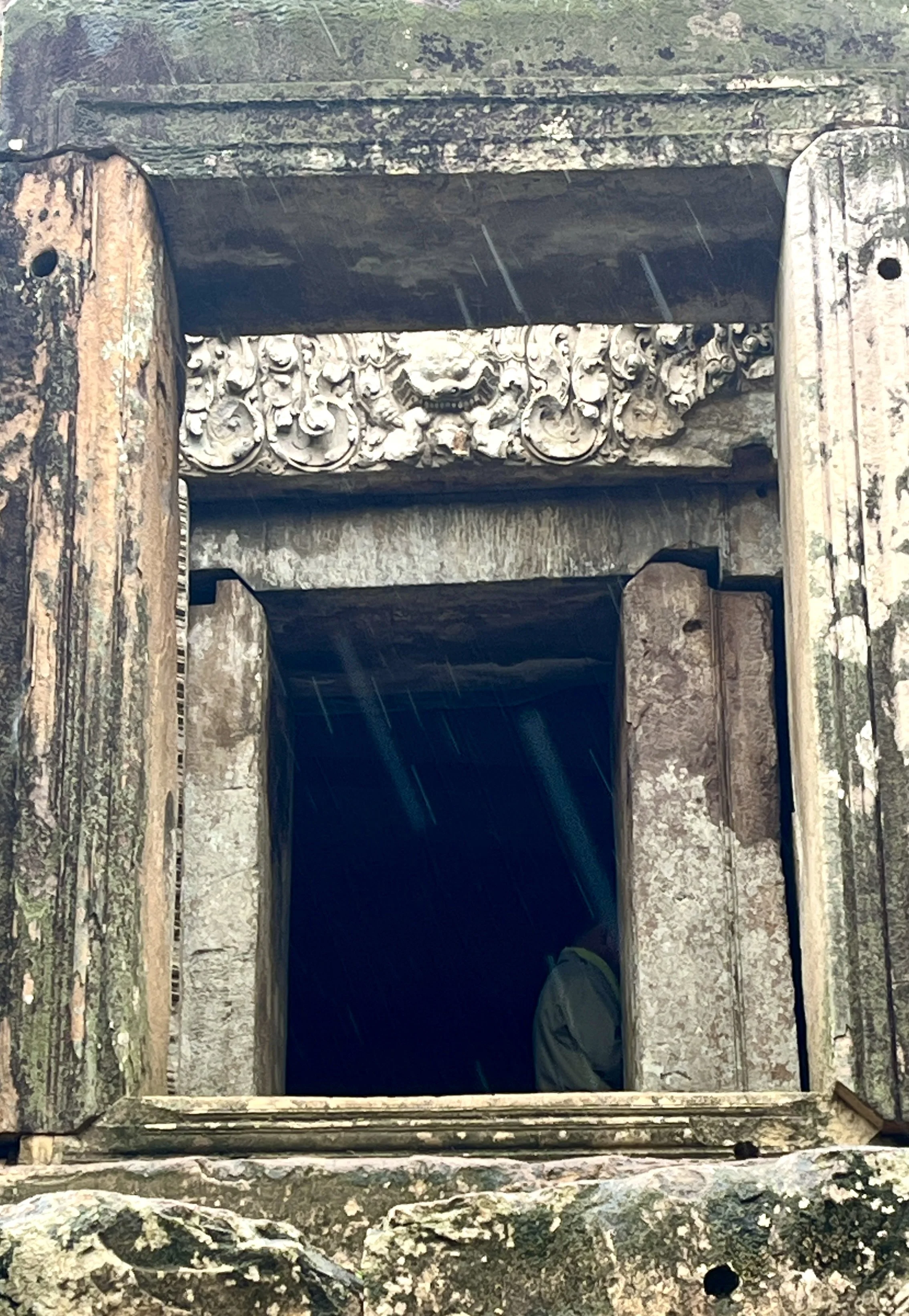

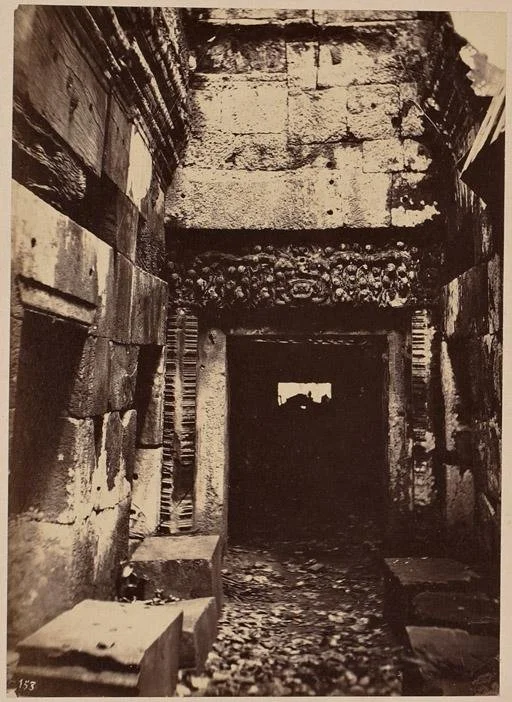

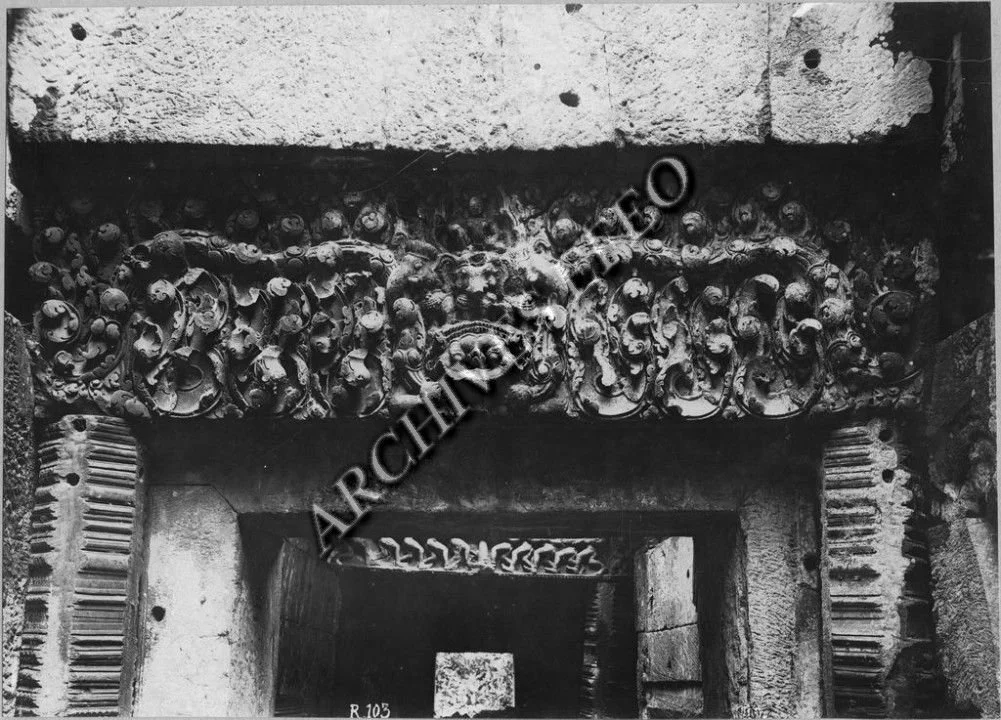

Battambang, as one of the historically wealthiest regions of Cambodia, has over 300 functional pagodas, not to mention the many ruins. Among them, Samrong Knong was, prior to the Khmer Rouge regime, the most powerful local monastery, with large grounds and many buildings and stupas, new and old. It was originally constructed in wood in 1707, and there is apparently (though I failed to identify it) at least one extant building dating from the first decade of the 19th century here. There are various stupas dating to the last quarter of the 19th century. The “new” pagoda was commissioned in 1887 and completely in 1890; the “old” pagoda was reconstructed in brick and plaster simultaneously, and last renovated quite recently.

During the Khmer Rouge regime, Samrong Knong became a notorious interrogation/torture center and killing field. All these buildings are clearly mapped for visitors.

Far better photos are available, even on google maps reviews– these are all I managed to get because:

1. I kept going at the wrong times. Everything was always locked up: not just the temples themselves, which is regrettably commonplace, but even the museum and library that were supposed to be open. This happens in Cambodia; if no one is there they just shut up shop, not realizing/caring that it’s ludicrous to expect a constant flow of visitors at their ordered pair coordinate of location/awareness. I think Samrong Knong opens up to big tour groups, so perhaps join one if you really care to go inside.

2. The weather was dreary and I wasn’t feeling well. I caught some sort of dreadful up all night wondering if I should go to hospital type stomach bug in Battambang (I think it might have been fried rice syndrome), and showing up here only to miss the sites– not once, but twice– convinced me it just wasn’t meant to be. Wandering past a pond, an info plaque attested that this was the pond in which the human waste of Khmer Rouge prisoners was dumped in one half, while the well-behaved among them were permitted to bathe once a month in the other. Nauseating. I left.