Monks’ robes out to dry behind some chedi; the first thing you see coming through the back entrance

Wat Damnak’s grounds host a forest of chedis and tombs. The oldest chedis are supposedly from the 1950s.

I’m unclear whether these little houses are homes, offices, store rooms, combos . . .I’ve been to monasteries in other countries where the more venerable the monk, the bigger/nicer the house. They are interesting examples of vernacular architecture.

An overgrown tomb or perhaps Buddha’s footprint

Scientists believe the large ornamental pond may be a moat vestige from an Angkorian temple on the site, of which very few signs remain.

I’ve never seen the gate open, so don’t know what’s in the little house.

The tallest of the stupas (this) and the other ‘ancient looking’ stupas were built in the 1930s in the style of Banteay Srei, as a learning project with the monks, in collaboration with EFEO archaeologist Henri Marchal.

Henri Marchal at Banteay Srei in the 1930s

There are so many organizations and buildings on the temple grounds that it’s hard to know which is which. I believe this is the monastery offices and school.

The main vihear, or prayer hall. This building was constructed in 1935 under the direction of the Venerable Prin Tim, the monastery’s second abbot.

“Damnak” means palace; the temple buildings were built on what was once the land surrounding one of King Sisowath’s palaces from 1904 to 1927, hence the name “Wat Damnak.” However, no palace remains on the site. This photo is undated, but was taken on a Verascope Richard produced between 1895 and 1910 and printed on their supplied paper from that era. Given that records say Sisowath’s palace was only here from 1904 to 1927, and perhaps it took some years to use up all the film, it’s probably 1900s or 1910s, though possibly later. Given the scaffolding, perhaps it dates from the 1904 construction of the palace!

From the EFEO archives, this photo is tentatively dated 1927. This building is no longer extant. It’s simply labeled ‘cremation party'- either of a very prominent unnamed local person, or perhaps in honor of Sisowath, but without his actual remains- he was cremated in Phnomh Penh and his ashes buried in Oudong. This building was deconstructed, removed, and rebuilt elsewhere in the city sometime before 1935, but has since disappeared.

This shot of the cremation cortège as it arrives at the temple shows just how open the land used to be. Nowadays it’s in the dense city center.

The younger the novice, the more they relish learning how to bang the drum. The little kids are swinging well above their heads! The most exciting part of their day is when they’re allowed to bang the drum for the 5pm chants. The monks here are very casual about it- they let the kids bang away at will for around 15 minutes, then slowly filter into the hall.

Also, though it seems an unimportant afterthought to a Westerner, the two hybrid Ionic/Angkorian columns are one of a kind in Cambodian temples.

The 4 original sandstone sema stones are still within the hall, demarcating the sacred space/ritual site. These stones are common to Theravadin Buddhist halls in Cambodia, Sri Lanka, Laos, Burma, and Thailand.

Scenes from the Reamker are carved on the shutters.

At the back entrance, three Angkorian artifacts are displayed: a pair of guard lions and a sandstone tub some believe was originally a sarcophagus.

As shown in these 1935 photos from the EFEO archives, if there was ever any carving or embellishment on this tub, it had become completely invisible well over a century ago.

Angkorian lions. It is unknown whether they were unearthed on the site at some point, or brought from within what is now the park grounds. Most believe they originated at Angkor Thom and were relocated by Henri Marchal in 1935-1937.

They didn’t immediately strike me as the most ancient/valuable things at Wat Damnak, but they are, by far. Photos from wikipedia; I somehow breezed by them twice.

Great example of Cambodian style art deco.

I’ve been daydreaming about a new construction bolthole/retirement option. I want something a bit grand, but also not too big and easy to build. Although I like the stilted wooden houses favored by locals, I have found several small inconveniences that make them annoying to live in: the tall precarious steps are annoying in the rain and with luggage; the vaulted ceilings are sort of grand and aesthetic when left open, but impossible to air condition. The solid brick and plaster construction and possibility of using standard-size windows and doors in a building of this style, and knowing locals know how to properly build it, makes it look like a safer option- I can literally point out this building and say build me that! and then embellish with plaster, carved wooden details, paint and plaster colors, awnings, gardening etc. I think it’s also a better shape to put a porch and pool out back.

Originally built in 1922-1923 as barracks for French troops, it now serves as a conference hall. It’s not a large building, but the proportions are grand. It’s sort of begging for plasterwork, colorful tile, a whole different colorway . . .

This house also features the most elegant rain drainage system I’ve seen, essential in Cambodia. So many yards are lumpy and waterlogged.

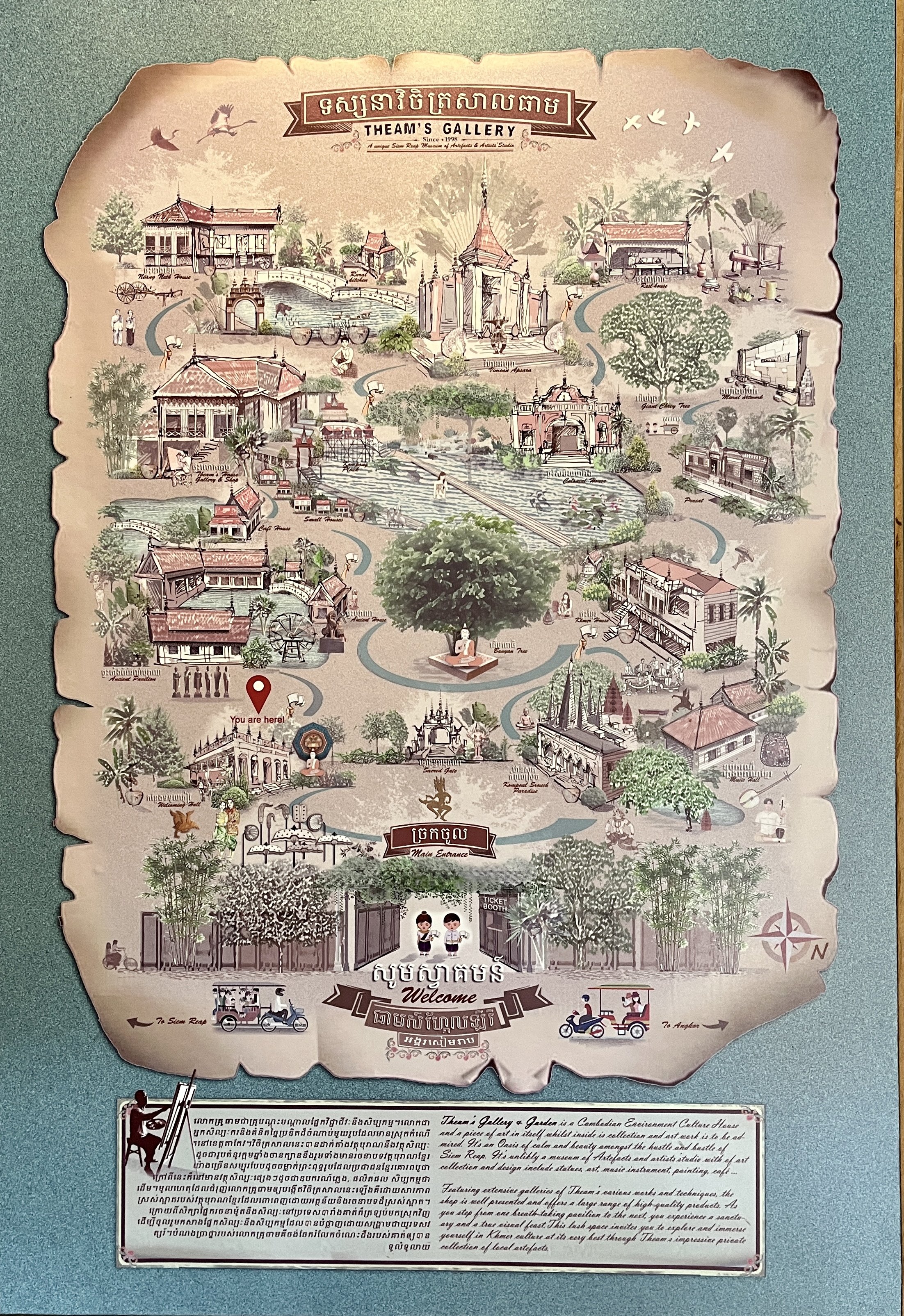

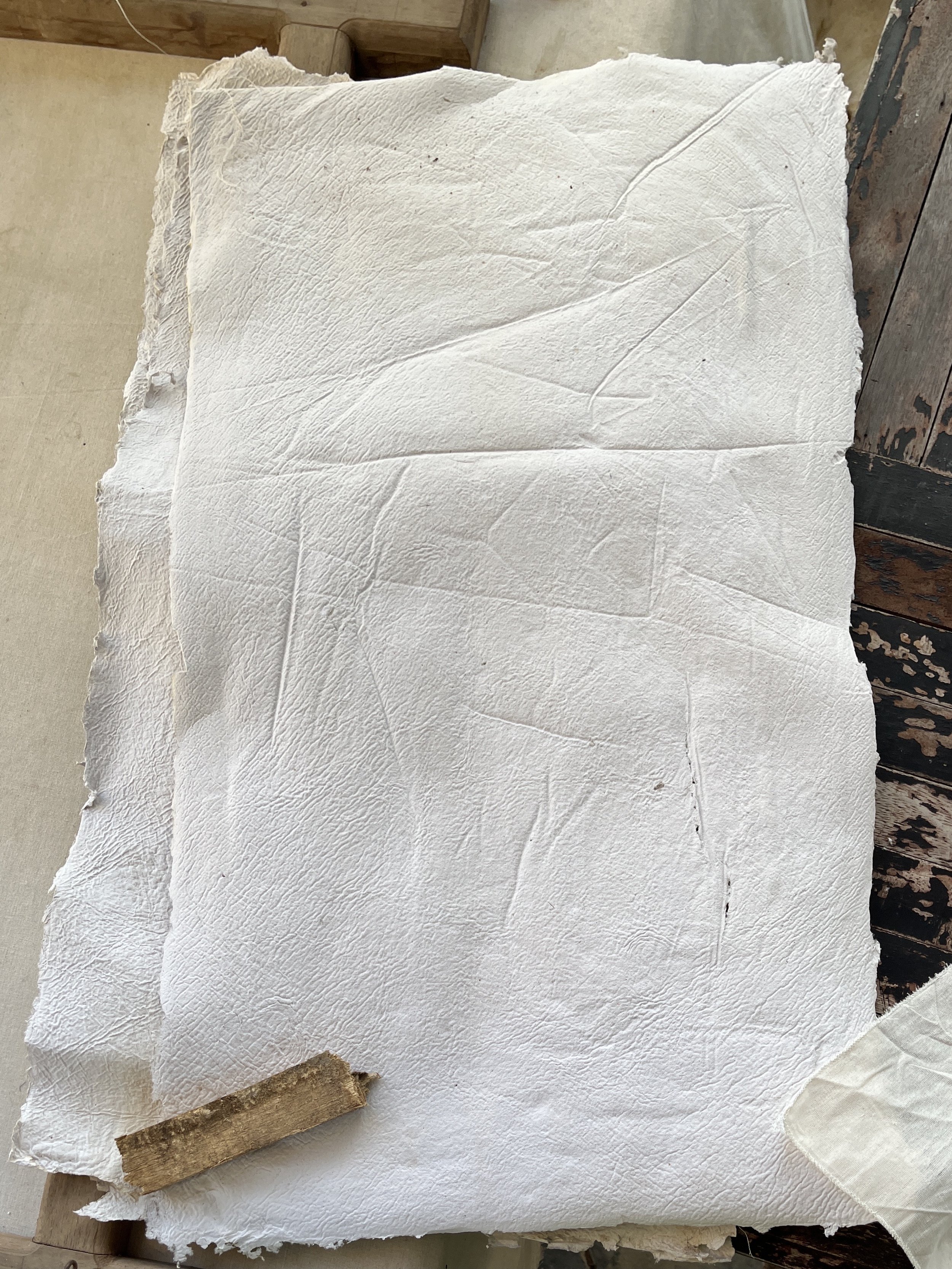

This is the modern library. It’s quite small and holds a very limited collection. It has the look of a converted old school or worker housing, but actually dates from 2010. The design maximizes airflow in an effort to preserve the books without air conditioning or other climate control. Of course that’s a slowly lost battle, but it didn’t seem to me there were any uniquely valuable books here. Of course, I could be wrong about the rarity of some of the old French tomes. I believe only redundant copies of EFEO bulletins are kept here, at least I hope so.

The view from under the giant old tree

I wonder where they got and how they choose their books.

If it were a bookstore, I’d definitely have bought these. Thankfully, they seem to all be available online for free:

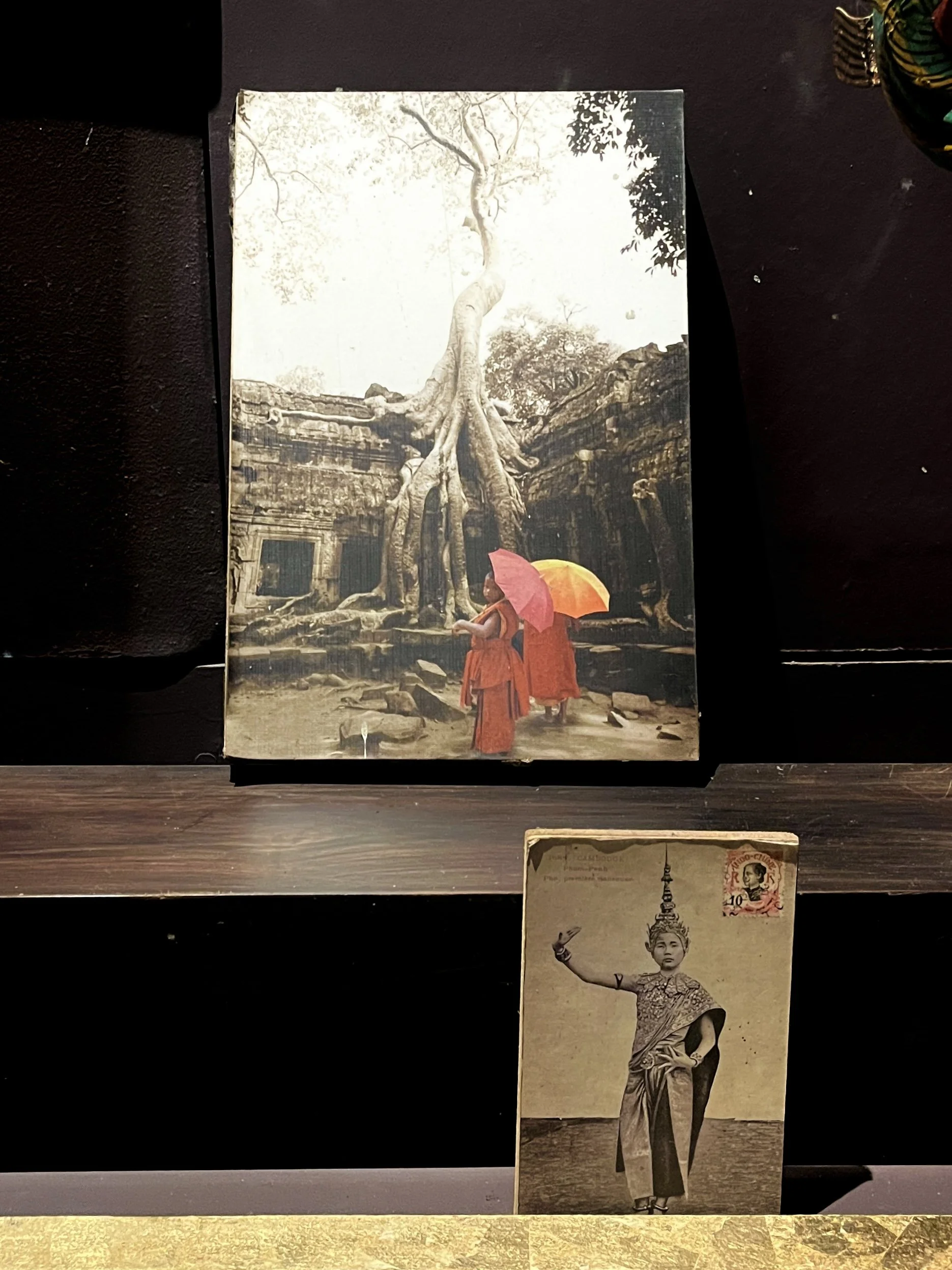

Danseuses Cambodgiennes par Georges Groslier

They had almost what I was looking for when writing my post about Kbal Spean: a later version of Jean Boulbet’s paper and map of the site. Turns out the reason there are missing maps/charts online is because they’re not there in person either; they must only be with the older version of the paper, if they are extant. Perhaps I’d be able to find it at the EFEO centre; their library is also open to the public.

Some late ‘70s photos from the bulletin- Jean Boulbet bottom left.

The backside of the reading room; there’s no reading area in the library itself.

I took several photos of the fascia and its trim, and the column capitals. They are an interesting combination of Khmer design and Western application. This building dates rom 1941, and I wonder if the trim was copied from the barracks building or vice versa. I’m guessing the barracks building was originally quite simple and trimmed up to match.

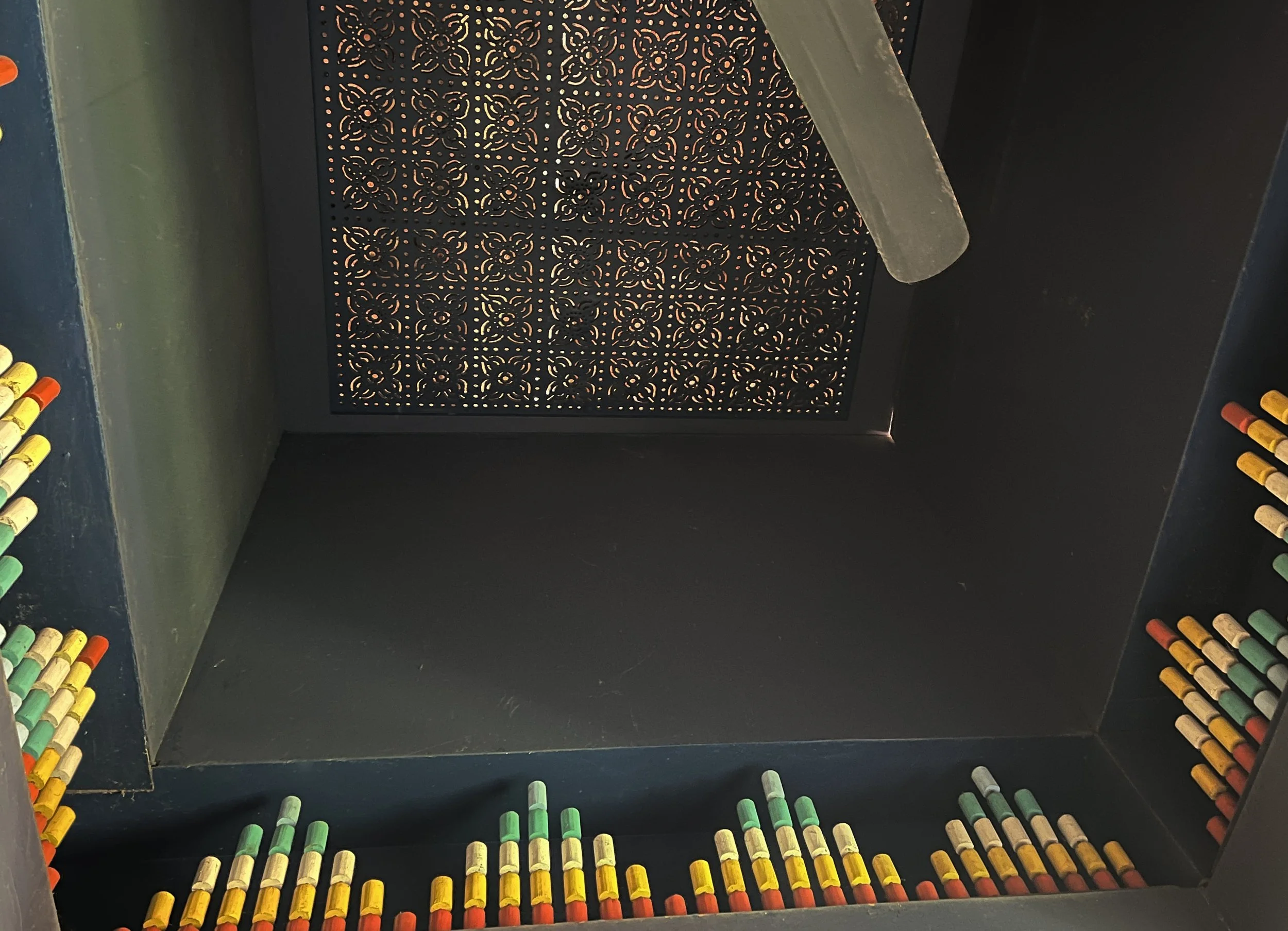

The plaster trim inside the reading room. I find the uniquely Khmer style interesting.

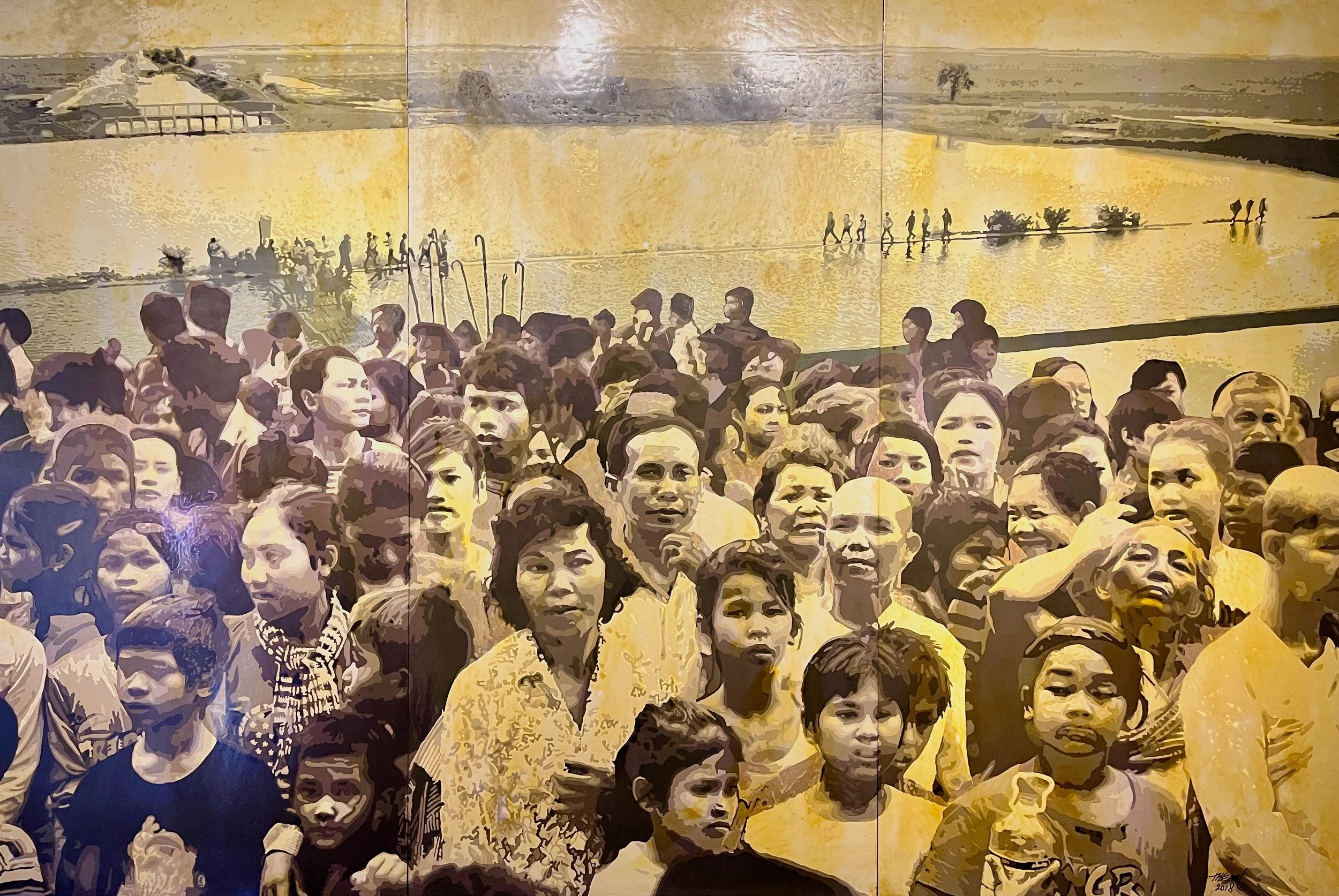

That’s not some ignored damage from a hook that’s been pulled out, it’s a bullet hole left over from the Khmer Rouge occupation. For the entire war, 1970-1975, the frontline was just a mile north of what is now the Raffles hotel, then the Grand Hotel d’Angkor. When the Khmer Rouge won, the population of Siem Reap was displaced to the countryside, and Wat Damnak became Khmer Rouge HQ in Siem Reap. The heads were chopped off most of the statues, and the original Buddha statue sitting here was (obviously) shot in the face.

Every single little frolicking animal in the painting has been shot in the face. The monks were forced to renounce Buddhism and join the Khmer Rouge, and shocked people by wearing guns with their robes. It’s no wonder this building was left abandoned and fell into disrepair after the Khmer Rouge left in the early ‘80s.

It’s easy to look up books and articles on their computers in the reading room.

They also have books for sale; looks mostly to be works by CKS scholars and redundant decommissions.

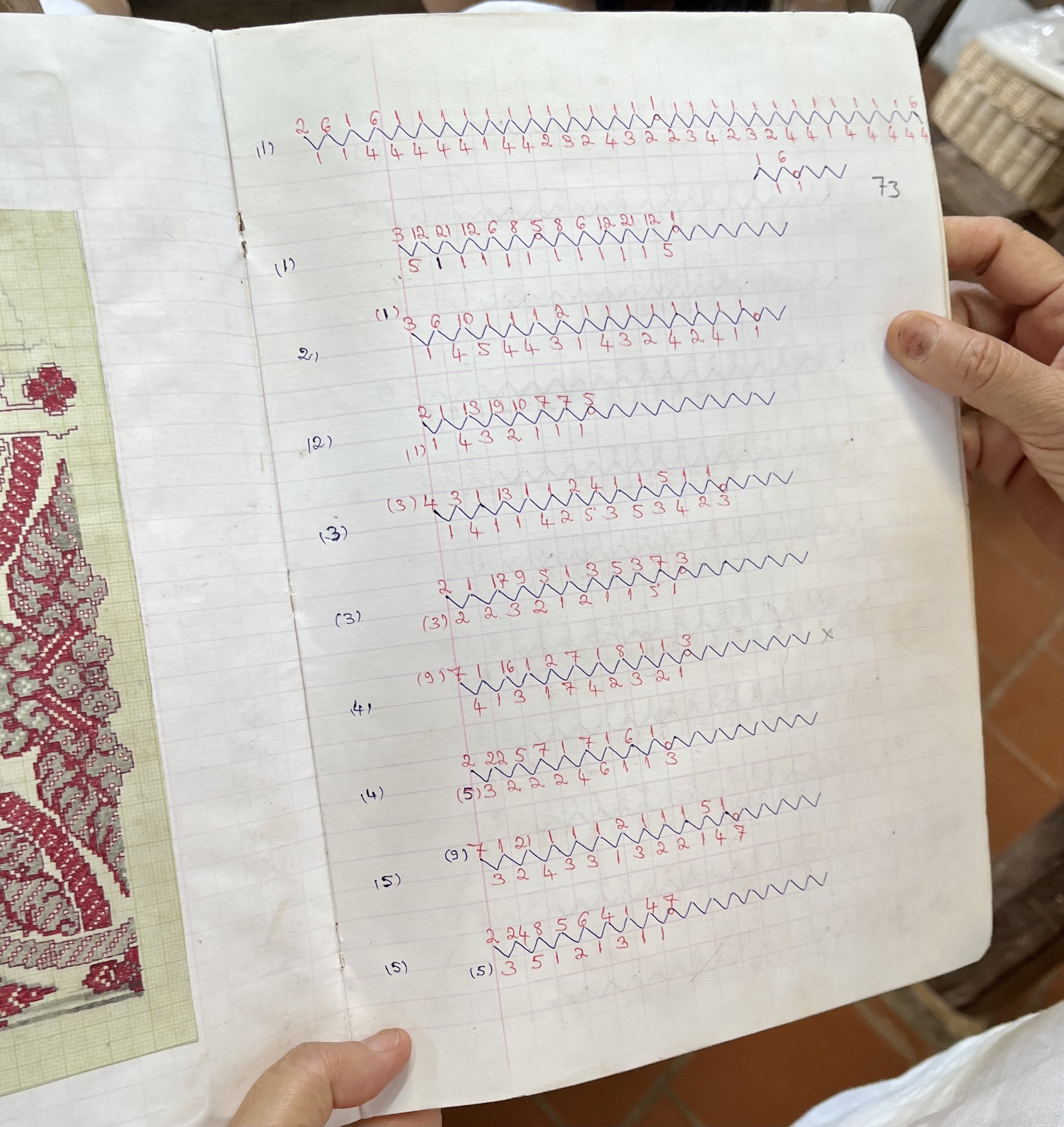

Very useful info that couldn’t be found online!

Originally the building was constructed as a Buddhist primary school. It’s smallish inside, but the exterior is rather grand.