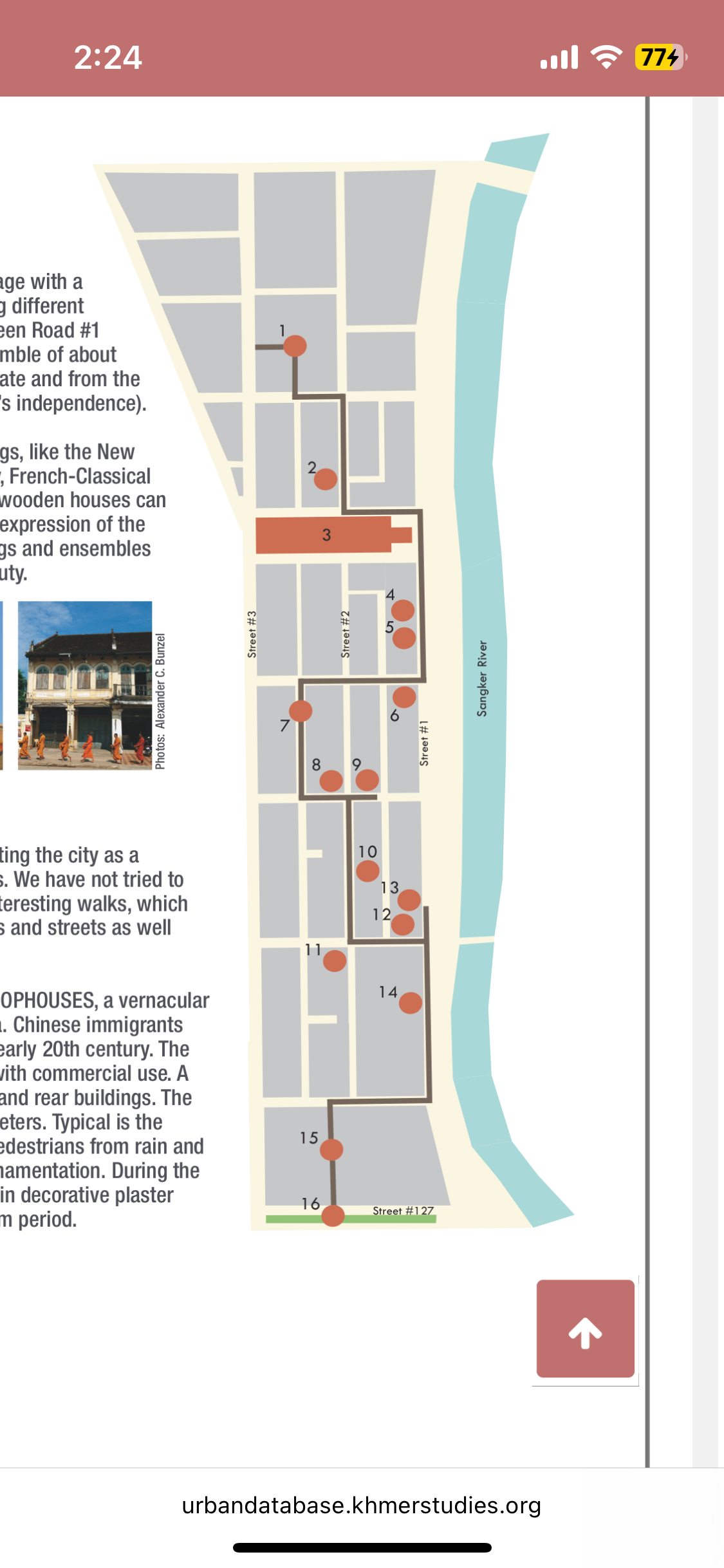

According to the hotel, La Villa was constructed in 1933 as the private residence of local ‘tradesman’ Eap Heo, and lived in by his descendants until the Khmer Rouge takeover in 1975. When the Vietnamese defeated the Khmer Rouge and occupied Battambang in 1979, they made this their local headquarters. When the Vietnamese left in 1989, the building was alternately leased or squatted in until it was sold to the present owners, “a young expat couple”, in 2004, and following renovation opened as a hotel in 2005.

We all know young expat couples can’t actually purchase property in Cambodia, so who knows what the truth actually is– I’m guessing at least one member of said couple is the K visa kid of refugees in France, or maybe the Cambodian kid of a corrupt government bigwig who studied and married abroad. Over the decades since Pol Pot died, these types have scooped up anything nice, setting up as landlords and hoteliers, many continuing to live in Europe while collecting rents here.

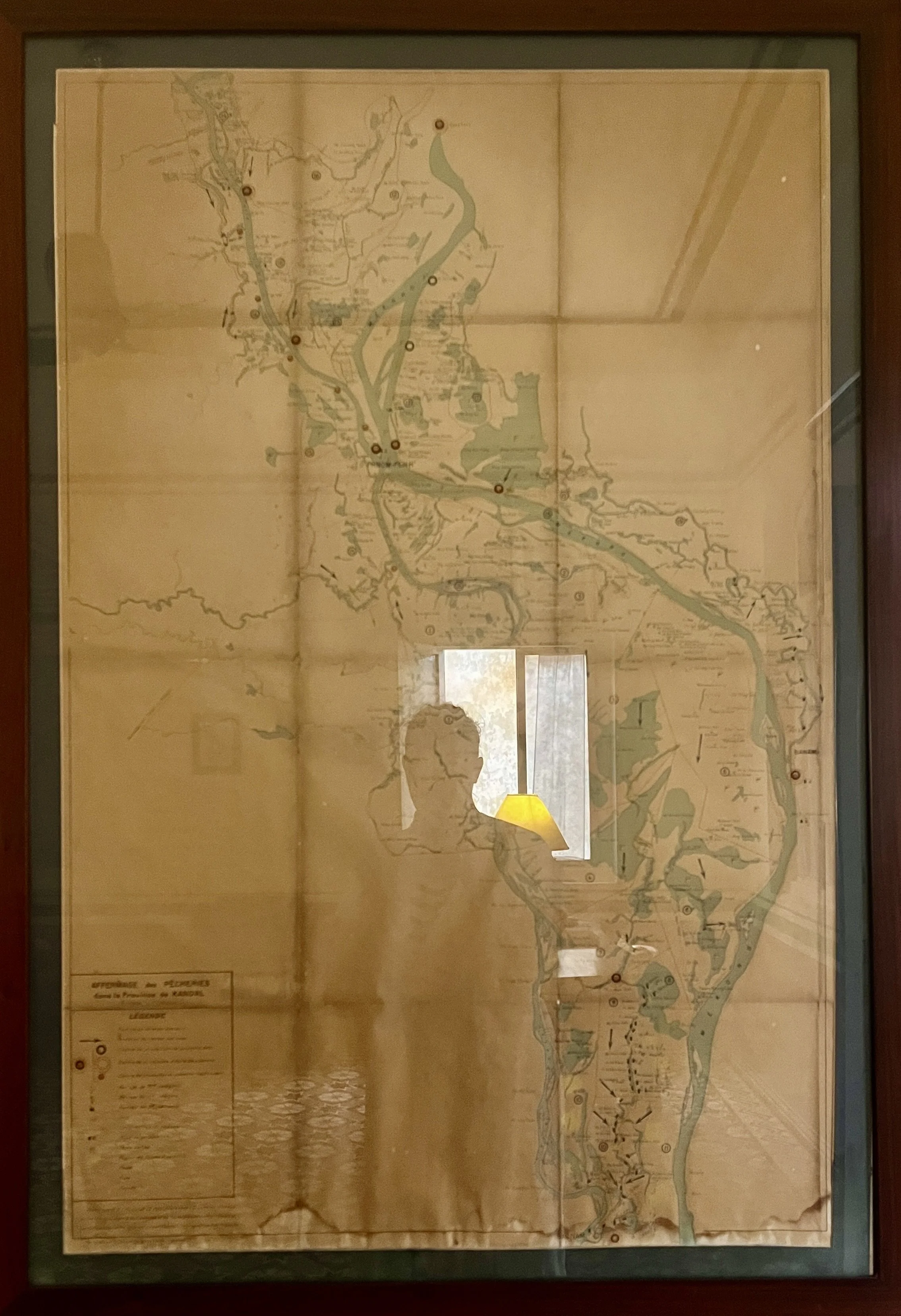

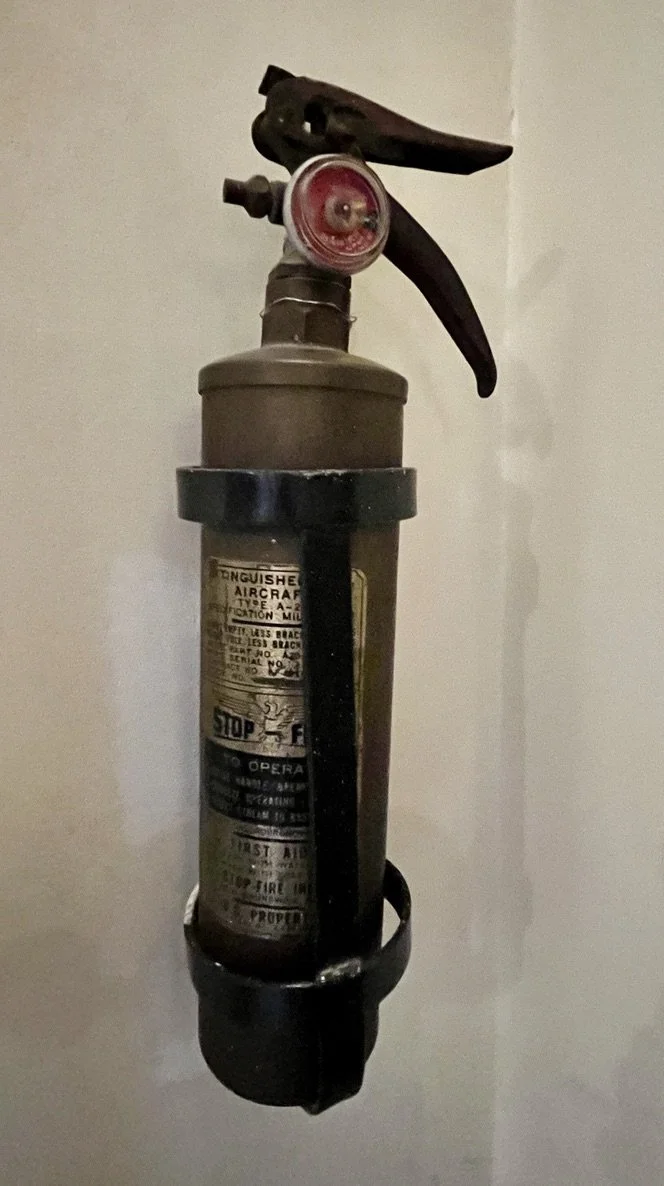

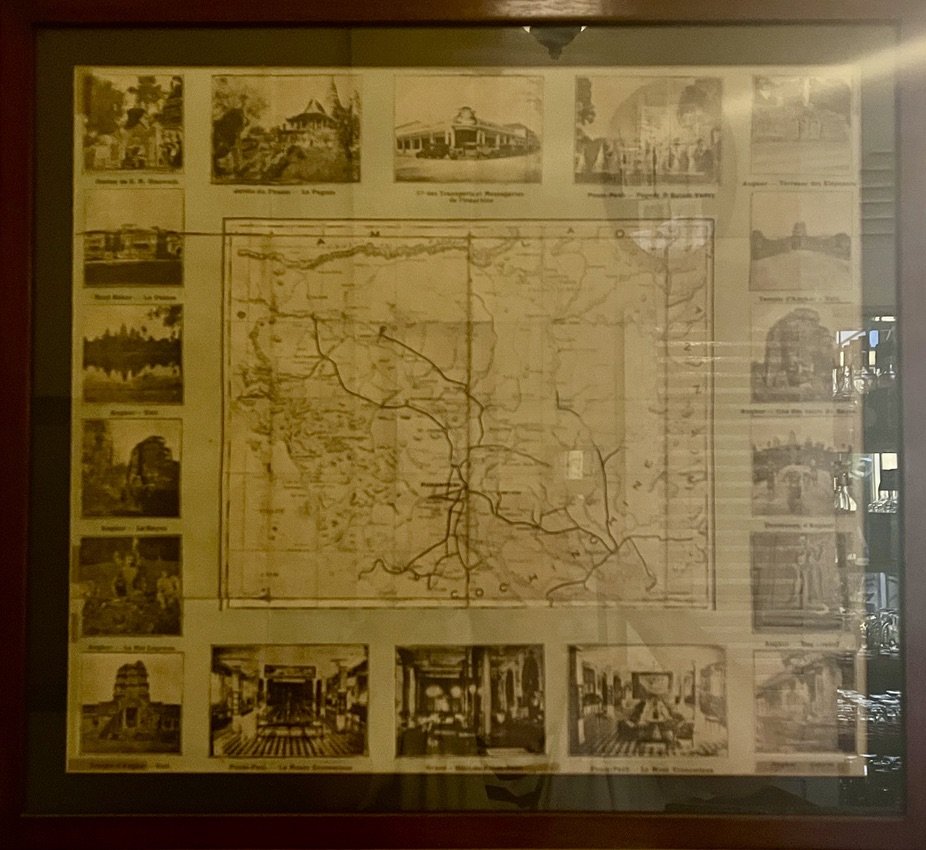

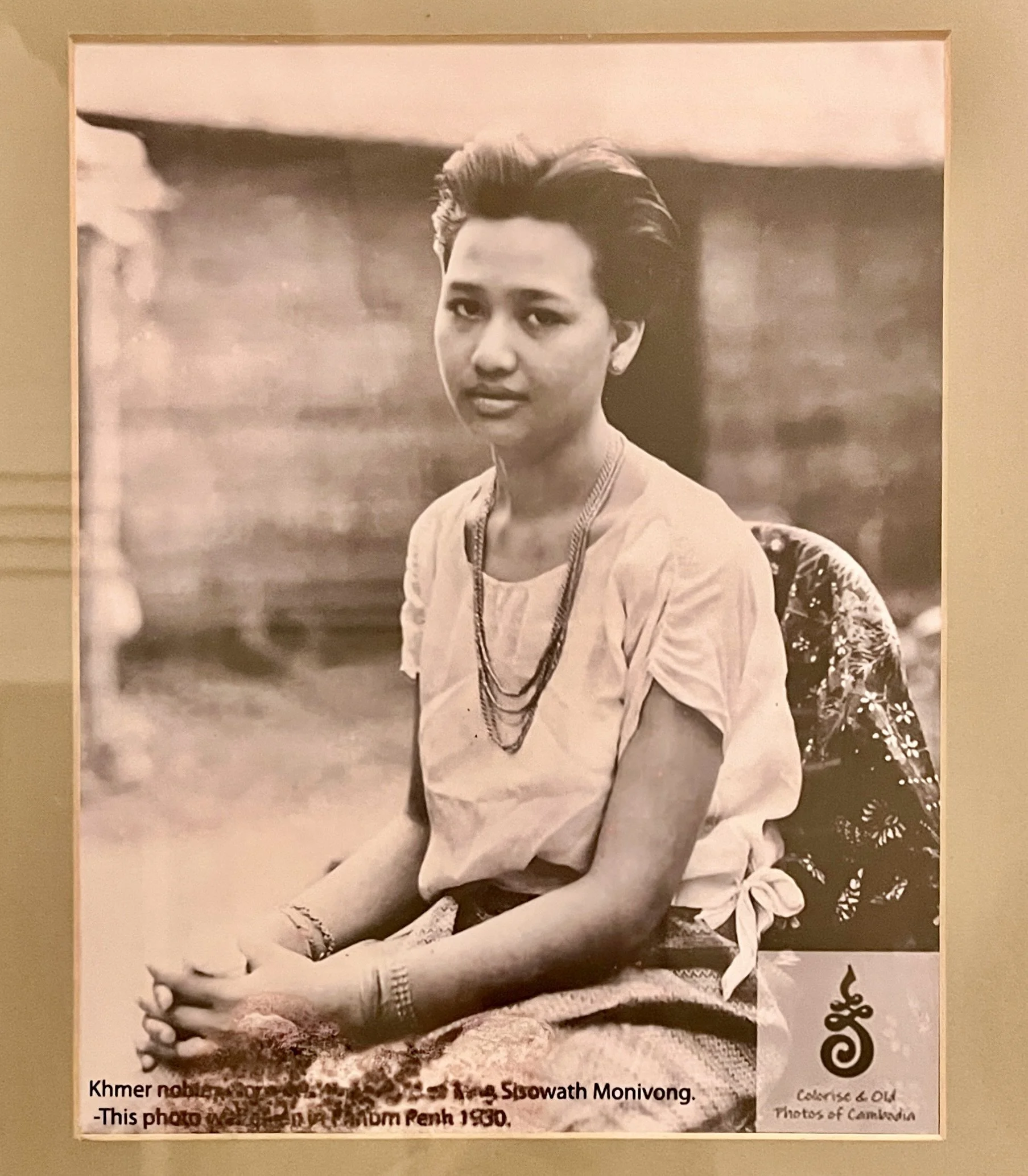

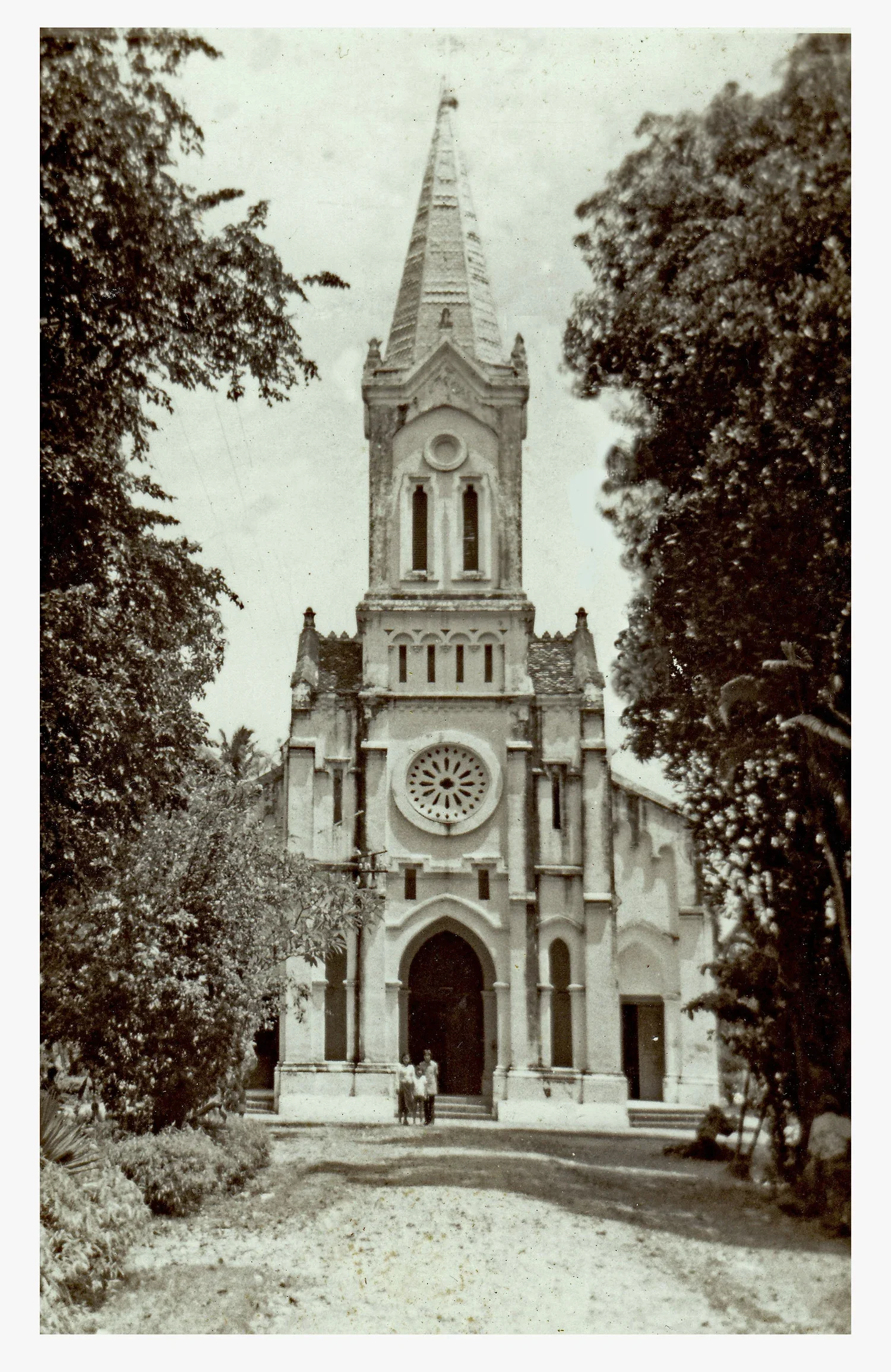

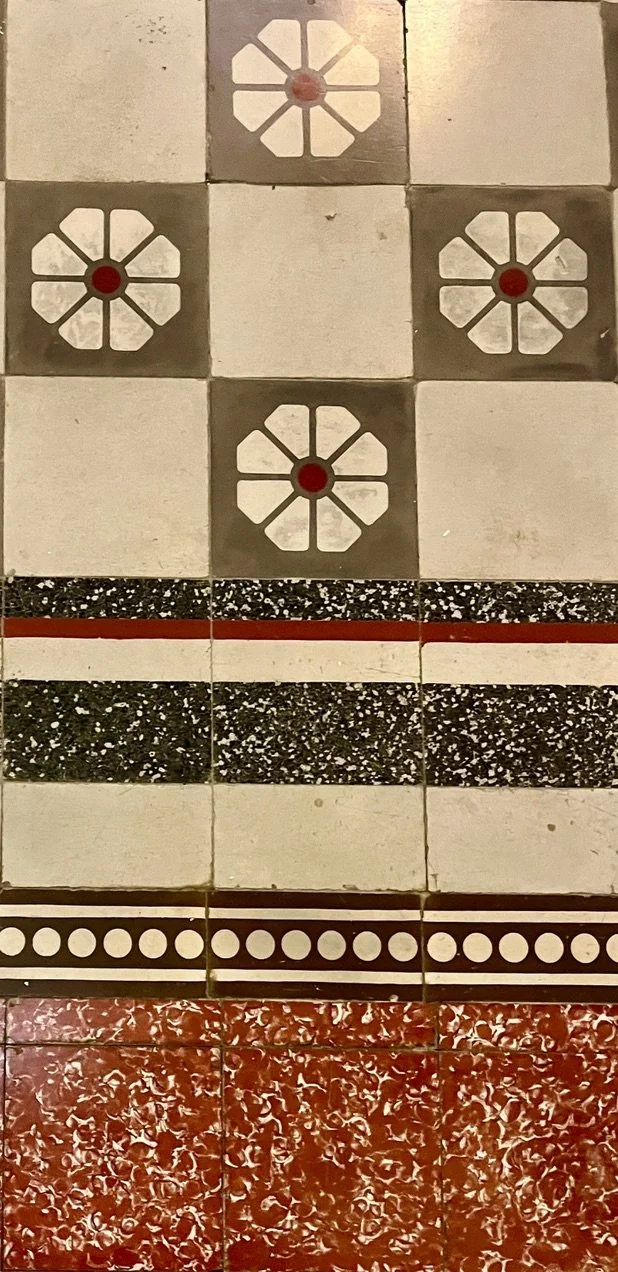

I really like that the renovation was more like a restoration, with period-perfect details and decor. It really feels like stepping back into the late 1930s; everything but the pool is accurate enough to be a movie set. Well, I guess there’s one minor caveat– all the antiques etc. are Vietnamese, not Khmer. However, as I’ve written before, after the Khmer Rouge, there are few if any surviving Khmer antiques (not looted artifacts). Zero pretense has been made towards inauthentic generic “luxury” in the style of Raffles, and I really like that. On the other hand, housekeeping is really not up to snuff; the rooms were very visibly dusty, smelled vaguely of either stale cigarettes or mold, and the linens etc. have clearly never been refreshed. It reminded me a lot of Loire valley 2 or 3 stars I stayed in as a teenager in the ‘90s.

In terms of service . . . not good enough. There were assholes smoking in front of my bathroom window and the concierge refused to ask them to stop or move– he did the standard SEA act of pretending to ask them not to smoke, then coming back to me and denying they had. When I told him I saw it with my own eyes, smelled it with my own nose, and wanted them and the furniture they were sitting on moved away so it didn’t happen again, he again, according to what seems to be a standardized SEA playbook of bullshit for hoteliers, refused to confront them, instead offering to move me into another room, as if I was the problem. I had paid for their most expensive suite– and therefore shouldn’t be inconvenienced, and certainly not downgraded– but was forced to choose another lesser room because the head staffer refused to confront the offending guests.

Same thing with the restaurant– instead of seating smokers far away from other guests outside, they let them sit right next to the glass doors, and left the doors propped all the way open, not caring if people purposefully sat inside in order to not be disturbed by smokers. It’s not an issue of not getting it, it’s an issue of not caring. Any complaints are answered with feigned ignorance, lies, and malicious compliance, it’s so, SO gross. I’ve been in SEA long enough to expect this nastiness rather than be surprised by it, but it still disappoints and disgusts me every time.

The restaurant is overpriced but reliable. The cocktails are fine. My favorite thing about this place, other than its architectural integrity, is how few other guests were there most of the time. It’s the kind of place I’d like to buy and turn back into a private residence.