Occasionally I visit a place that’s simply not worth the entrance fee, and this is one.

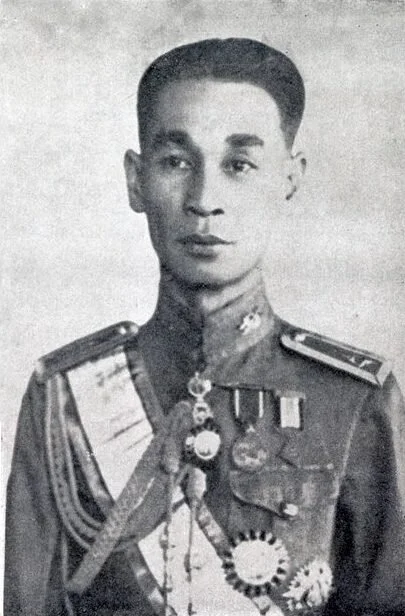

Lord Chhum Aphaiwongse

Commissioned by Lord Chhum Aphaiwongse in 1905 from Mario Tamagno (best known for the Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall at Dusit Palace), this is as close to a simple template of a French colonial style mansion as could be conceived, the SEA base model McMansion of a hundred years ago. It’s an almost eery feeling; I’ve walked through this exact house, all over SEA, smaller or larger, with only slight differences.

Lord Chhum must not have seen the Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907 coming. In 1904, Siam gave France Trat in exchange for Chantaburi. In 1905, Lord Chhum commissioned the house. In 1907, just as it was completed, Siam got Trat back by trading in the Buphaphon, the area including Siem Reap and Battambang that the Aphaiwongses had hereditarily governed since 1795.

The Aphaiwongses, originally local warlords in far southern Treang, rose to nobility and wealth with Siamese backing in the latter half of the 18th century. When local Cambodian chiefs went to war for Cambodian puppet kings supported by either Siam or Annam, the Aphaiwongses supported, and were supported by, Siam. When the Nguyens became distracted by the Tay Son rebellion, Siam got the upper hand in Cambodia, culminating in the first Aphaiwongse Okhna, Chau Baen, serving as regent over the Cambodian child puppet King Ang Eng.

1773 map by Thomas Kitchin

Over time the court in Oudong divided into those who wished to continue with the current line of puppet kings, and those who preferred to just give Chau Baen Aphaiwongse the throne in his own name. To prevent civil war in Cambodia, and/or the rise of a formidable rival, Siamese King Rama I recalled Chau Baen from Oudong, but raised him to the nobility and awarded him the hereditary governorship of Battambang, Siem Reap, and Sisophon, to defend and administer as annexed Siamese territories.

Thai King Rama I

After the 1907 treaty, the French offered Lord Chhum, the sixth generation ruler of Bupaphon, to stay on as their governor in Battambang. However, like his ancestors, Lord Chhum again chose loyalty to Siam, moving his family to the Bangkok court of Rama V (Chulalongkorn) after the handover. Briefly installed as the governor of Prachin Buri, he had the Tamagno house built for him again there, hoping to entertain Chulalongkorn in style. Other than the window shapes and plaster appliqués, everything was exactly the same. Unfortunately Rama V died before the house was finished.

The Prachin Buri twin house

When Lord Chhum’s granddaughter eventually married Rama VI, becoming the Princess Consort of Thailand, Lord Chhum gave them the Prachin Buri house as a wedding gift. Unfortunately Rama VI died before Princess Suvadhana could have a son, so the throne passed to his younger brother . . . and the Prachin Buri house remained unoccupied. At the outbreak of WW2, Suvadhana and her daughter fled to England, remaining there until 1957.

Princess Suvadhana

Because Thailand allied with Japan in WW2, Suvadhana’s father Lueam officially became the last Abhayavongsa governor of Buphaphon during the period Japan occupied Cambodia, from 1941 through 1945– though he still never lived in the Battambang house, which was used as Japanese army offices.

Khuang Aphaiwongse in the 1930s

Meanwhile, her older brother Khuang served as Prime Minister of Thailand three times between 1944 and 1948. After the war, he remained the leader of Thailand’s Democratic party until his death in 1968. Suvadhana had a royal funeral in 1985, and the family is still considered noble/royal in Thailand.

The most impressive thing about the place is the grounds. Large grassy lawns with manicured trees are rare things in Cambodia, it’s typically either city living or a waterlogged mess.

Another colonial era building on the grounds.

There are several government office buildings in one corner of the grounds.

I like the chevron brickwork.

Inside is both inauthentically renovated (lol at that layered drop ceiling) and as dull as possible.

The ground floor is occupied by what they think passes as a museum. It’s the most pointless, random assortment of mostly vintage objects.

A jumble of bad, mostly recent furniture.

Horrid door that has clearly had things ripped off at some point.

Are they trolling?

Built in features have mostly been ripped out, but there were 2 bookcases like this.

I wonder if it was never quite finished because the family knew they’d never move in, or if things were ripped out at some point.

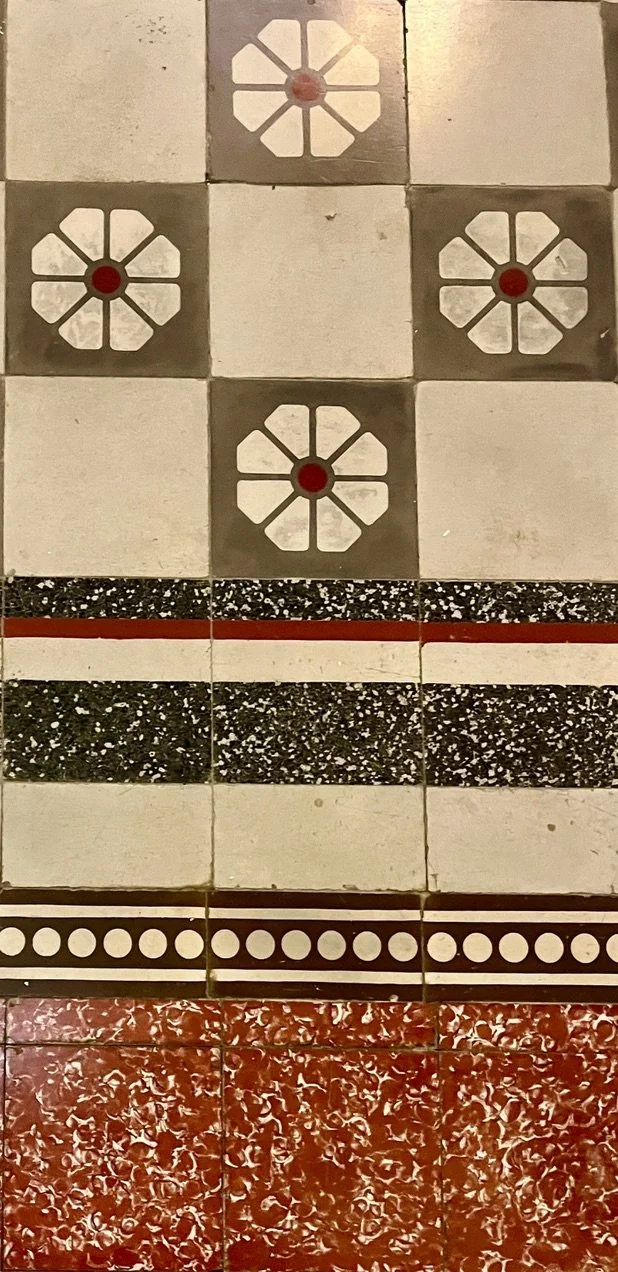

Hard to tell if these are original tiles or not. I think mostly, but there is a huge jumble in this building. The pretentious polyester curtains really bring out the depression of it all.

I don’t even know why I took this picture. Despair? Wanting to remember the dimensions should I ever install shutters?

The performative shrine of course.

I guess some people will pay to rent traditional clothes and do a little photo shoot here?

I took lots of pictures of the tile border combos for inspiration

Weird assortment of farm equipment and housewares.

Hard to say because nothing was translated, but I think these were the personal hobby instruments of famous people?

Likewise, hobby shooting items?

There are a bunch of old photos.

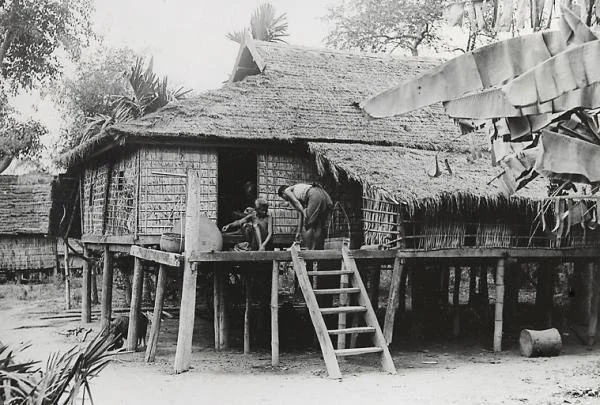

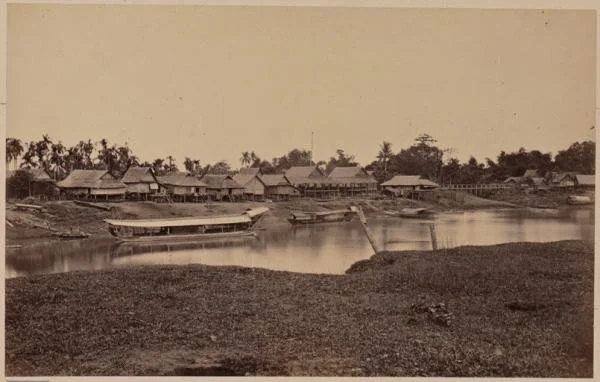

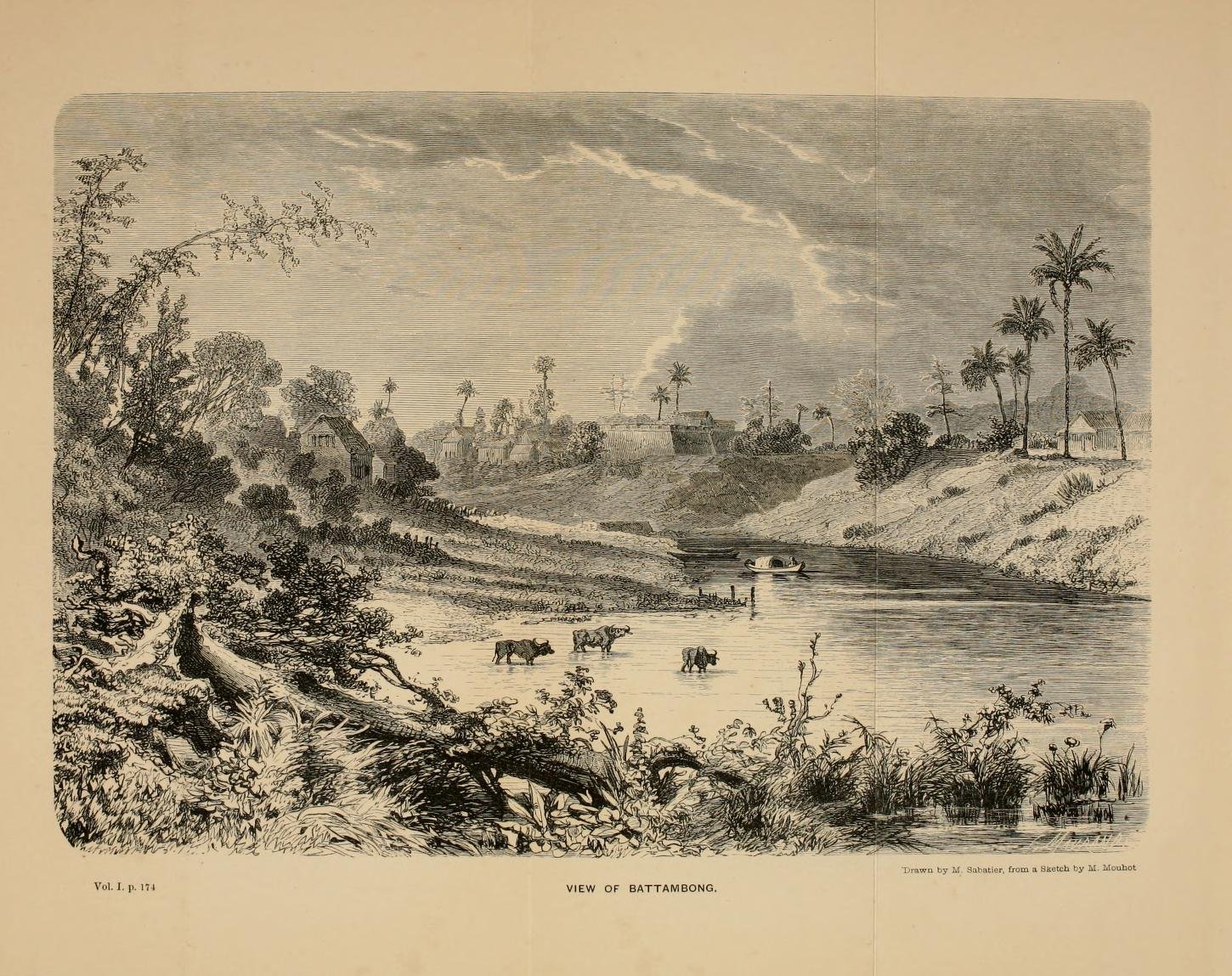

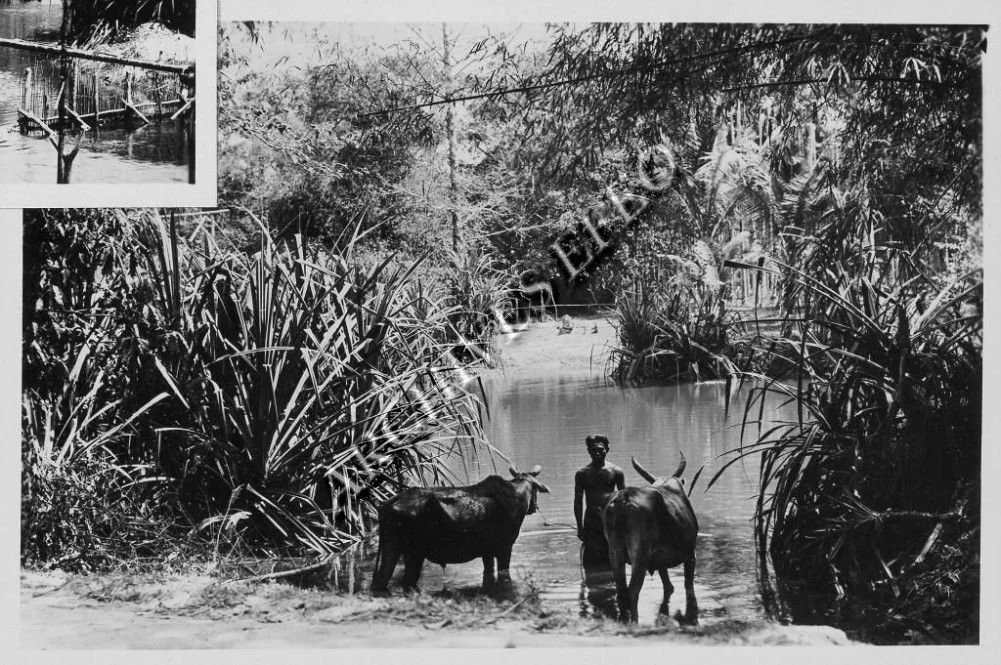

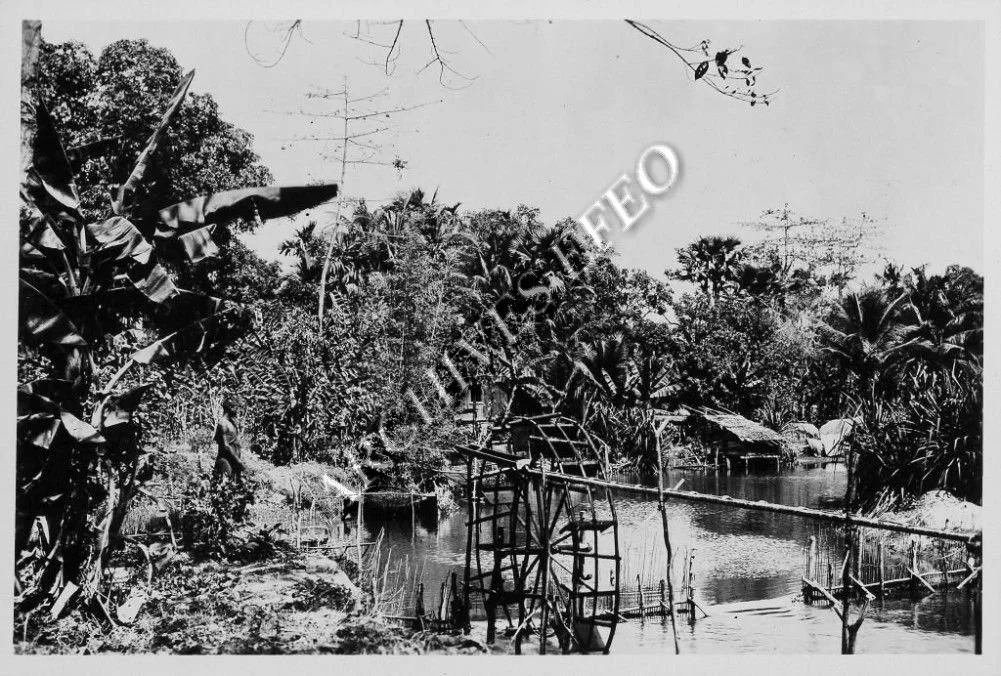

This view is not much different today.

Are these cowbells? Are these cowbells in a display cabinet or am I losing my mind?

Not particularly fond of this style but it’s growing on me.

Why are these things in a museum?!

It’s always struck me as strange how local museums in Asia have “antiques” so much worse than literally anything in my grandparents’ very middle class homes in New York.

It’s a custom for court women in Thailand and Cambodia to wear a specific color every day of the week.