Models of various traditional Khmer house types at Mrs. Bun Roeung’s House

Wat Kor village, 2km south of Battambang proper, was the neighborhood historically chosen by wealthy Khmers a century ago. Today, it is best known for its 20ish heritage houses showcasing local traditional architecture; 20 years ago, it was best known as the hometown of Brother Number 2, who was born in one such house in 1926 to wealthy Chinese immigrants.

The house is still there, but no one will tell you which one it is; there’s no photo identifying it online; in person and search results the laughable party line is “the house no longer belongs to Nuon Chea’s family; it was purchased by a local resident in the late 1980s from someone else.” Who else? In the 80s, when everyone was squatting and no one had any kind of ownership documents, or money to speak of? Battambang was held by the Khmer Rouge by turns until 1996.

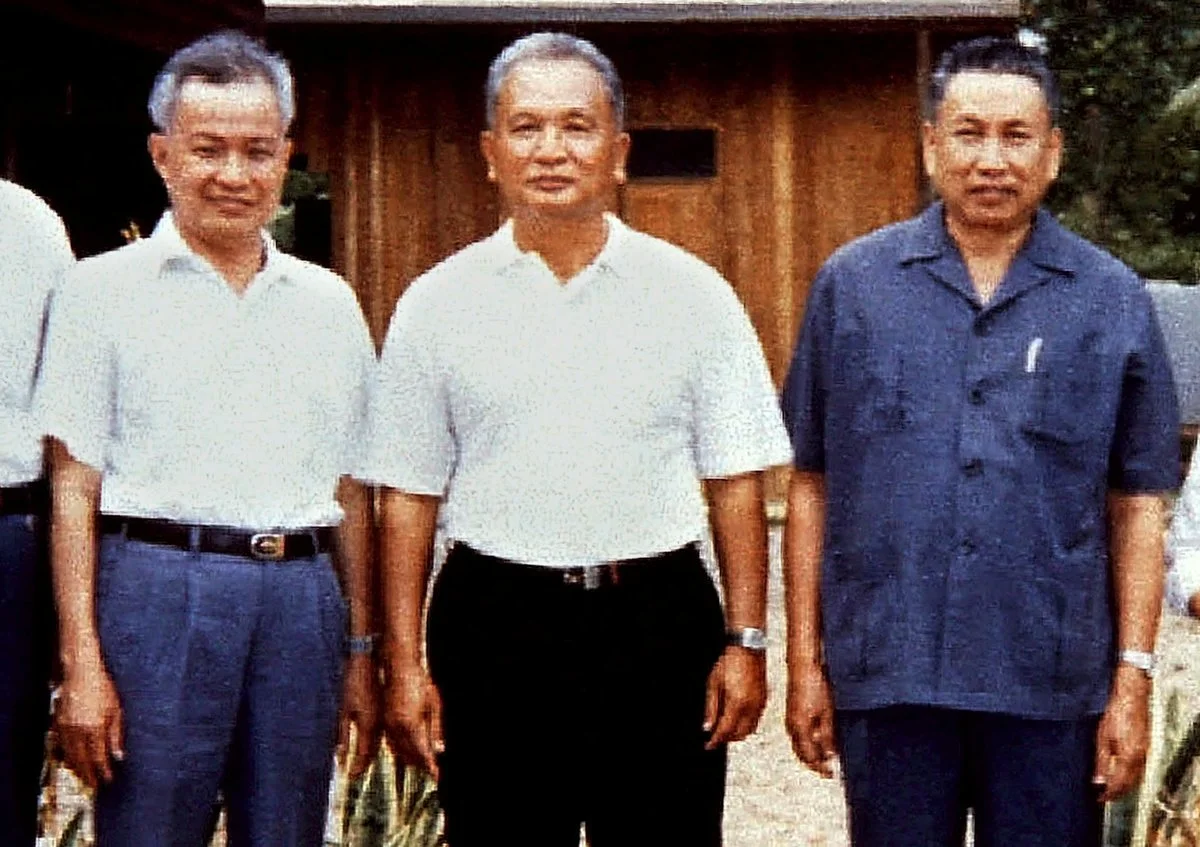

The Khmer Rouge leadership in 1986: Khieu Sampan, Nuon Chea, Pol Pot

No matter, I was there for the architecture. And that architecture may have been at least partially preserved because Batttambang– and Wat Kor village specifically– were occupied BY KR top brass.

In photos of well-to-do villages dating from the 3rd quarter of the 19th century, the houses tend to have walls of woven grass and thatched roofs, but the bones of the regional architecture are the same: stilt houses with square layouts and gabled roofs.

The wealthier houses featured front or wraparound porches covered by a second lower roof, and a connected outhouse for cooking. These photos were taken by Émile Gsell between 1877 and 1879.

In photos taken 30 to 40 years later, so around the same time the heritage houses of Wat Kor village were constructed, anyone who could afford to was building out of wood rather than woven grass– having even a small wood house became preferable to a large grass one.

But the layout remained the same, squarish with gabled roofs. You’ll also notice that at first, thatched roofs on wooden houses was the norm. These photos were taken by Léon Busy between 1926 and 1931.

A classic simple wooden house in Wat Kor village.

By the first quarter of the 20th century, anyone who could afford to was building with or renovating to tiled roofs. This is a great example of a house that was built with a wooden roof initially intended for thatch, but had tile laid over top.

As the local Thai colonial architecture became more formal and sophisticated, the gables shrunk, while the perimeter roofs, originally meant to cover just the porch, were made to cover more of the central house, for a more tiered Siamese look.

By the turn of the century, new houses were constructed to showcase beautiful tiered Siam style tiled roofs with cement finials. Decorative aprons became popular in the 1910s.

Another option when putting on a new tiled roof was a French style mansard roof. Enclosing the stilted area below the house also became the norm in the French colonial era.

Later houses feature a flattened rectangular layout better suited to showcase the tiers of the Siamese style tile roofs, and emphasize the central finial–usually a flame, but occasionally something else– I’ve seen some with the year inscribed.

The final iteration: extensively renovated with each decades’ favored modern “upgrades”– most noticeably the picture window and metal sunroof– this house is actually rather old. Yet, it is the template for most ‘Khmer style’ houses constructed today; the only dead giveaway here is the rather steep outdoor wooden staircase coupled with the enclosed ground floor– in a modern house, it would be one or the other, but not both.

Khor Sang House is one of the two in the village that operates as a museum. It was built in 1907 by the present owner’s grandfather, then a young secretary to a colonial Thai official. I wonder if, like the governor’s mansion, construction was begun here before the surprise handover to the French, or if it was built with the proceeds of a severance package. The proportions of the house are inconspicuous, but the owner standing in this photo gives enough of a sense of scale to appreciate how large the place really is.

Compared to pictures on google maps from 2018ish, there’s less furniture in the house than there used to be, so it looks a bit empty. The layout is the traditionally Khmer open square with some walled off bedrooms.

The high ceilings and oversized windows really give a feel of rustic grandeur.

The walls are wattle and daub– in Cambodia, that means layers of latticed bamboo and plaster.

The owner doesn’t speak English– only mile a minute strongly accented French. My French is poor, so it was hard for me to keep up! In his father and grandfather’s generations, most colonial administrators, lawyers, successful merchants, etc. were polyglots, speaking the Chinese dialect of their ancestors (usually Cantonese), Khmer, Thai, and French.

This made me laugh– must have been the money room!

Inside one of the bedrooms.

There’s a collection of bills from all over the world, cash donations tourists have made.

Around the house are some old household tools.

I found it interesting that a good half of the old furniture was locally made, rough hewn versions of European styles.

The walla aren’t decorated but for calendars, portraits and graduation photos. It is cheering to see a family who have valued education so highly over multiple generations.

I have no idea what this cabinet of curiosities is about, but it did make me smile.

The owner’s diploma from 1966. I always want to ask how someone like him survived the Khmer Rouge, but fear the answer, and don’t want to re-traumatize or offend either.

The original builders of the house, I believe.

The second heritage home open to tourists is Mrs. Bun Roeung’s house. She is also a third generation inhabitant of the house.

She speaks English, so I was able to pick up a lot more about the house’s construction and history. It was built by her grandparents in 1920; her grandfather was an Okhna and retired general, working as a lawyer when the house was built.

One thing that was emphasized to me, and is also visible in Yi Sarit’s house, is the mix of valuable hardwoods used in construction. The 36 structural pillars and roof frame are Phcheuk, the indoor floorboards are Beng and the outdoor floorboards are Korkoh. The design of the house is called “Pet”– with a wraparound verandah.

Right next door, visible through the window, is the smaller modern house the family currently resides in.

The walls are wattle and daub.

All the furniture is old. Some of it is not original to the house, but similar to what was once there and replaced by the owner. She said the original pieces are the biggest and heaviest; the Khmer Rouge stole everything that wasn’t too heavy to carry.

The original owners of the house.

According to the Battambang government website:

“The said ancient house is divided into three parts:

1st part: this part consists of the front and side verandahs.

2st part: this part is the middle part of the house, which consists of a huge living room. At the rear left side of the living room, there is a door leading to two bedrooms.

3rd part: in front of the two bedrooms, there is another door leading to a side verandah and the wooden staircase. At the left side about 5 meters from the door, there is a kitchen.”

She explained that in a typical eat-the-rich move, the Khmer Rouge turned this house, arguably the fanciest in the neighborhood, into the communal kitchen/place for storing heavy equipment and threshing rice. She says having big vats of water and porridge leaking onto this part of the verandah for years was what damaged the wood, and any lesser wood would have rotted completely.

The running water for the garden as it is today.

I’d love a pet turtle but alas, can’t have any pets at present.

Downstairs are some old tools for threshing rice, weaving fabric etc.

The cement stairwell is original; at the time, it was considered modern and stylish.