The Ho Chi Minh complex in Hanoi is probably the number one must-see place in the city. It’s made up of four main elements, and a loose fifth: the biggest draw is Ho Chi Minh’s Mausoleum, followed by the Stilt House, the One Pillar Pagoda, the Ho Chi Minh Museum, and the grounds of the Presidential Palace.

Most people line up to circle the preserved corpse of Ho Chi Minh himself, which is treated as a religious relic: encased in glass, in a giant stone vault with low lighting, and maintained by the same Russians that handle Lenin. No cameras are allowed, no hats are allowed; cleavage, shoulders and thighs must be covered, and a white-uniformed honor guard monitors everyone uncomfortably. One odd thing about it all is that Ho Chi Minh did not ask for or even imagine anything so gruesome at all, but if you're morbidly curious, check it out.

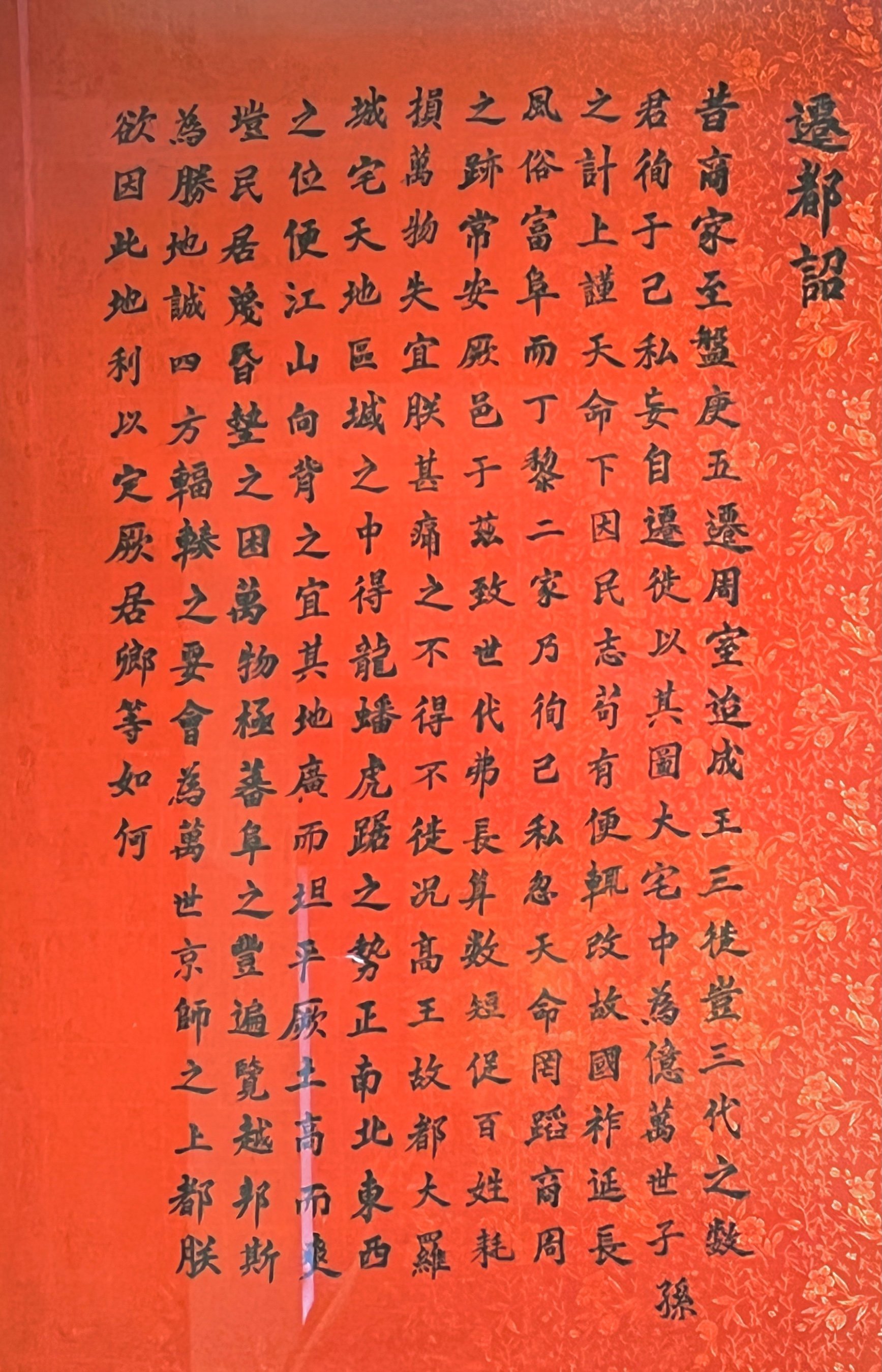

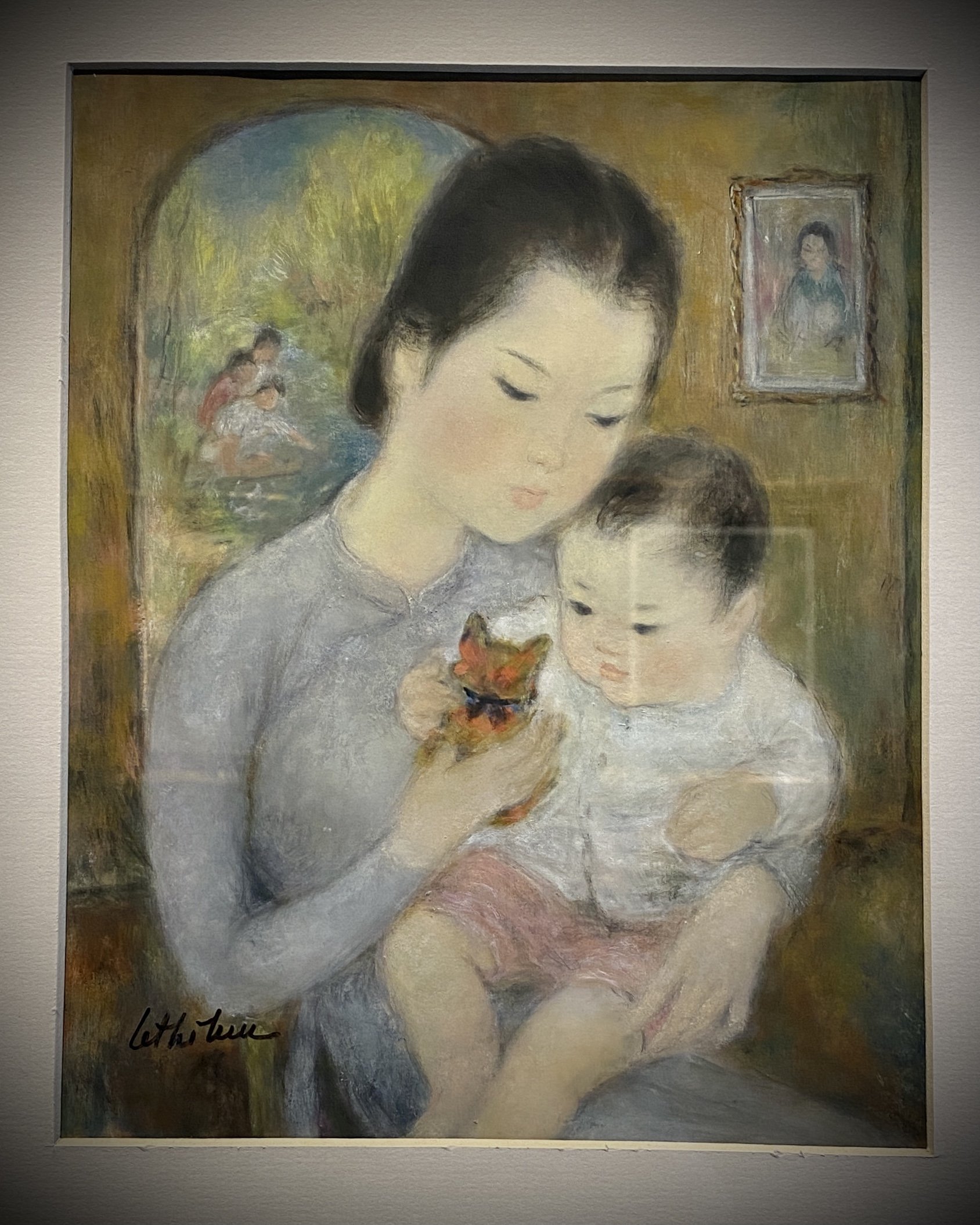

Speaking of Ho Chi Minh, his museum is way over-designed. It has the feeling of a 90s amusement park, but provides excellent insight into his life and philosophy nonetheless. The gist is that he grew up in a mandarin family, but his father lost his position in a distressing way. Realizing he wouldn't get a great education or job thanks to his dad's reputation, he traveled the world for 30 years, collecting ideas about political and economic systems of governance, and returned to Vietnam with three goals: independence, unification, and communism.

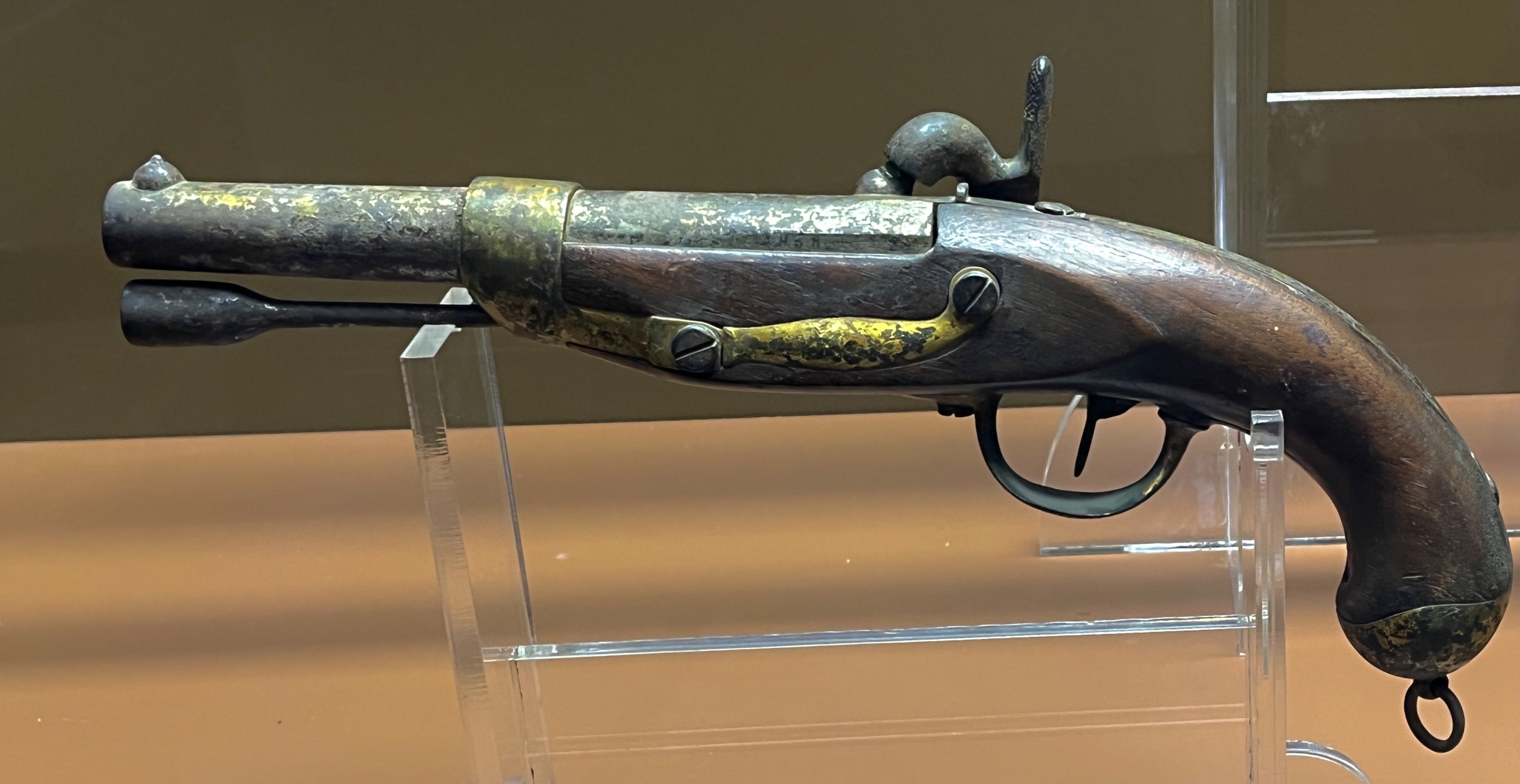

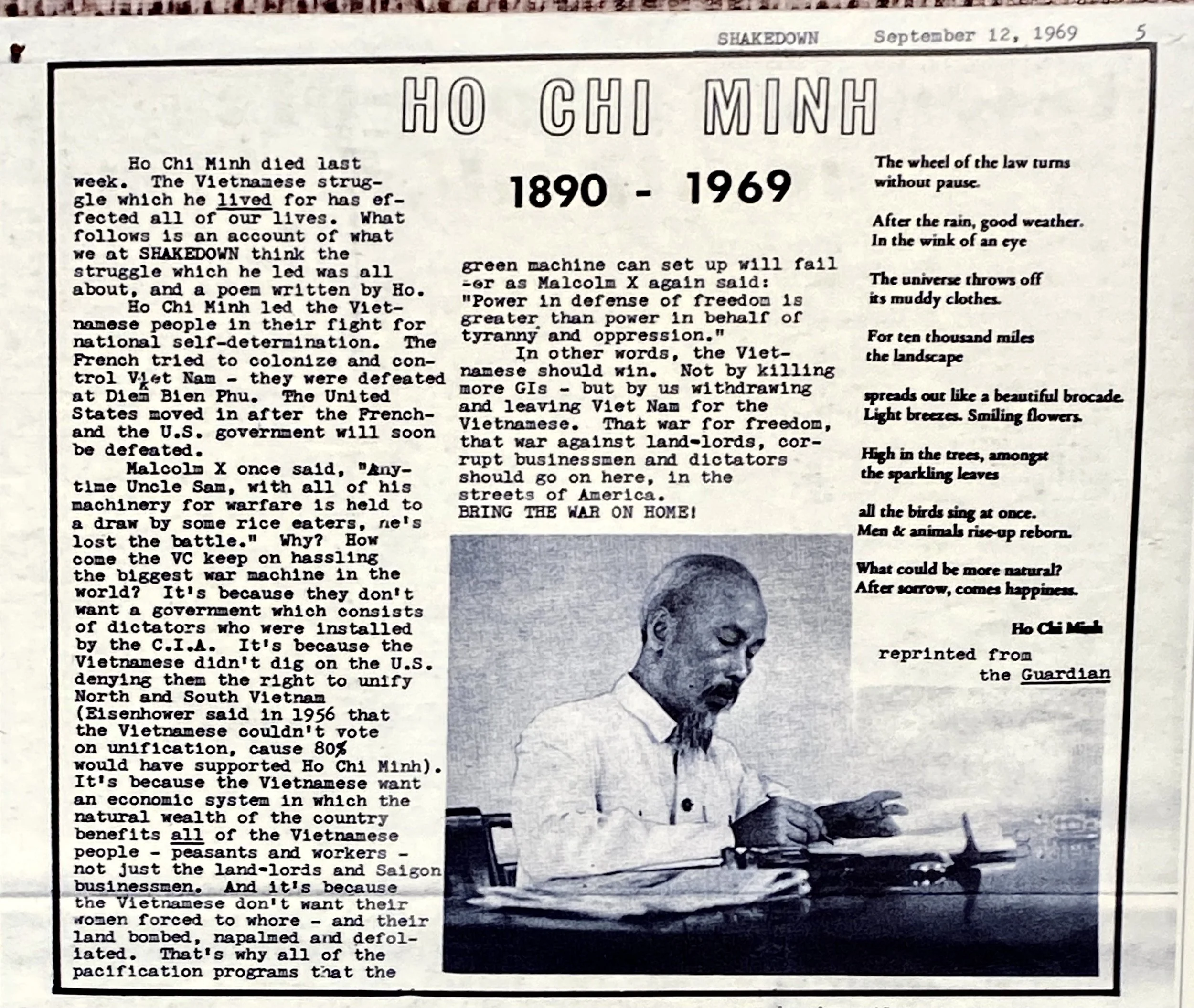

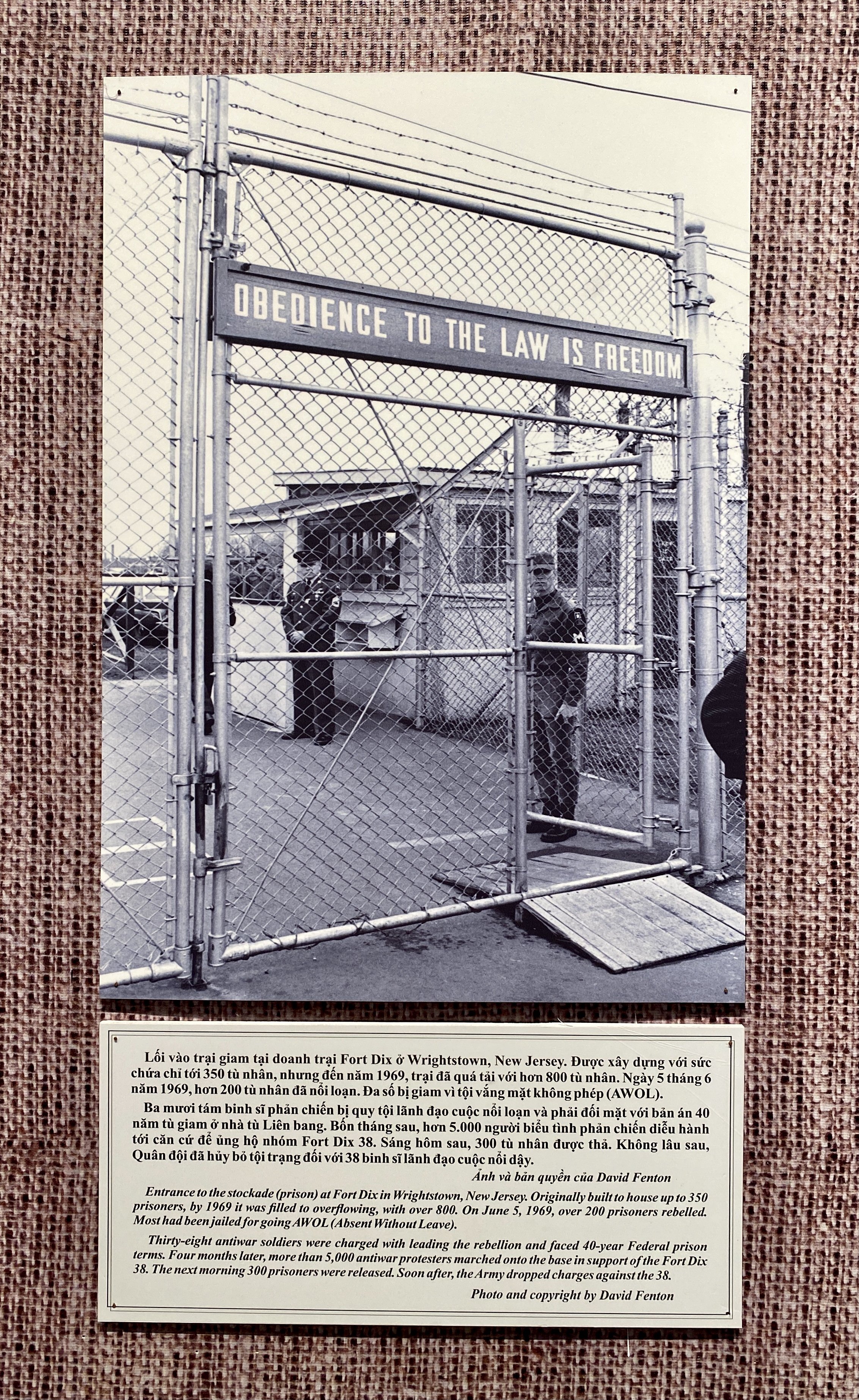

There are many museums in Hanoi covering the practicalities, if you will, of the Indochina and Vietnam wars, like the Ho Chi Minh Trail Museum, B52 Museum, etc., but if you're actually looking for the reasoning behind it, that's better understood here.

Just outside the museum is the One Pillar Pagoda, perhaps Vietnam's most famous temple. Originally built by emperor Lý Thái Tổ in 1049, the pagoda was the site of an annual royal bathing ceremony for hundreds of years. The original architectural concept is called a lotus station, wherein a hexagonal building recalling a mandala sits on a single stone column in the middle of a lake, resembling a lotus blossom, a Buddhist symbol of purity. Over hundreds of years and many restorations, the temple came to its final architectural form in 1840. The original building was dynamited in 1954, so what stands now is a 1955 reproduction of the 1840 building. Over the past 20 years, there has been on-and-off debate over replacing the building with a reproduction of the original thousand-year-old design.

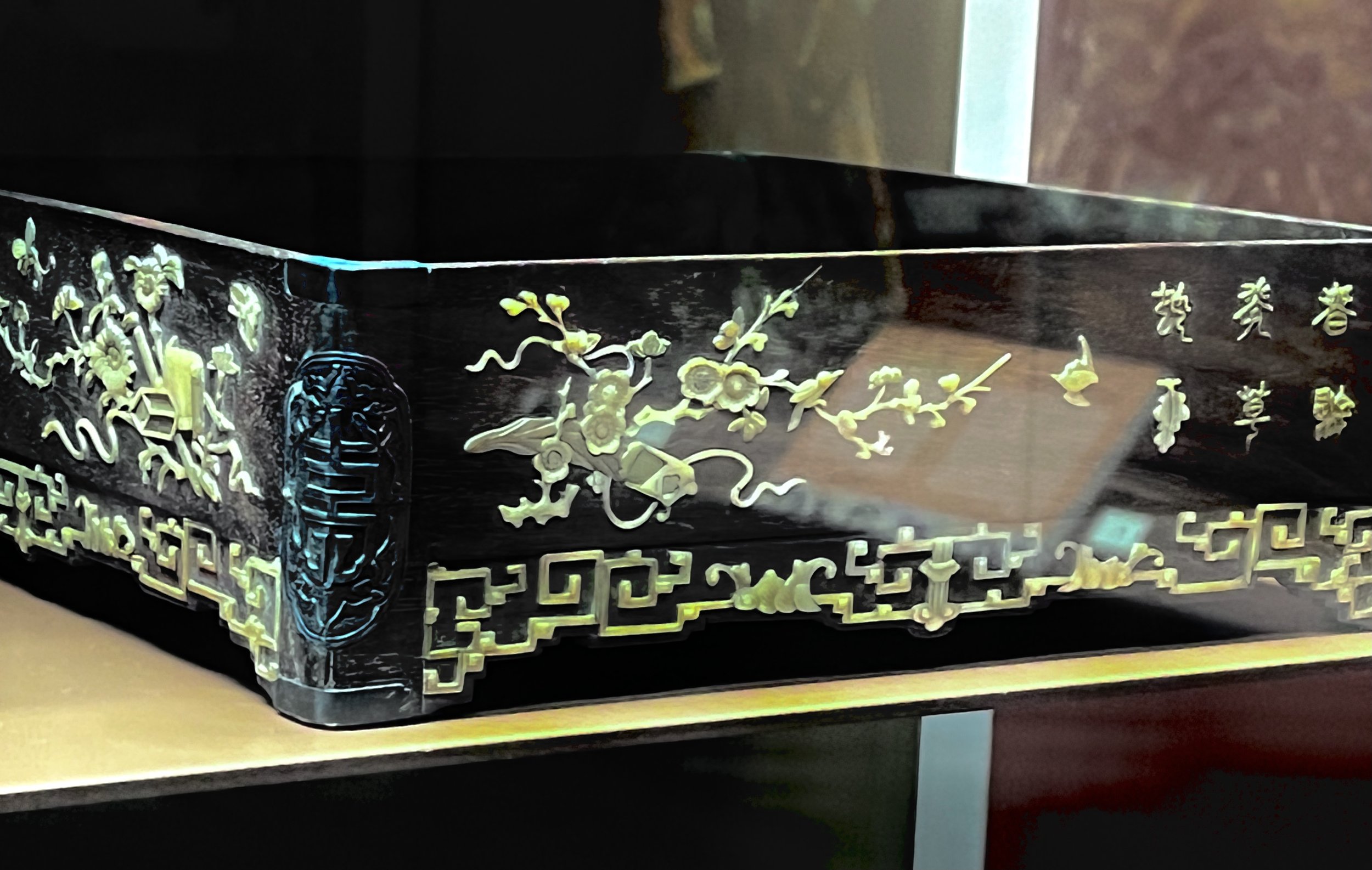

The Ho Chi Minh Stilt House, built in 1958 by architect Nguyen Van Ninh, is a modern super luxe version of the Tay stilt houses common in Viet Bac, where Uncle Ho built up the Revolutionary Army before taking Hanoi. It's both very stylish and very of its time; if you like mid-century modern, Danish modern, etc. you should really enjoy this luxe Asian version of it.

The last few displays are in the outbuildings of the Presidential Palace. The palace itself was built by Vildieu in 1900 as the French Colonial Governor’s residence, and is not open to the public; it's only used for government meetings. After taking Hanoi, Ho Chi Minh refused to live there because he felt the optics were bad. However, one of the outbuildings, romantically called House 54, served as his home and office from 1954 until the stilt house was completed, and there are some truly boring rooms to look into there. There is also a small local restaurant on-site and a gift shop with the most extensive inventory of communist memorabilia I’ve ever seen.